Childhood Domesticities: An Exercise in Self-Archaeology

Carlota Jerez

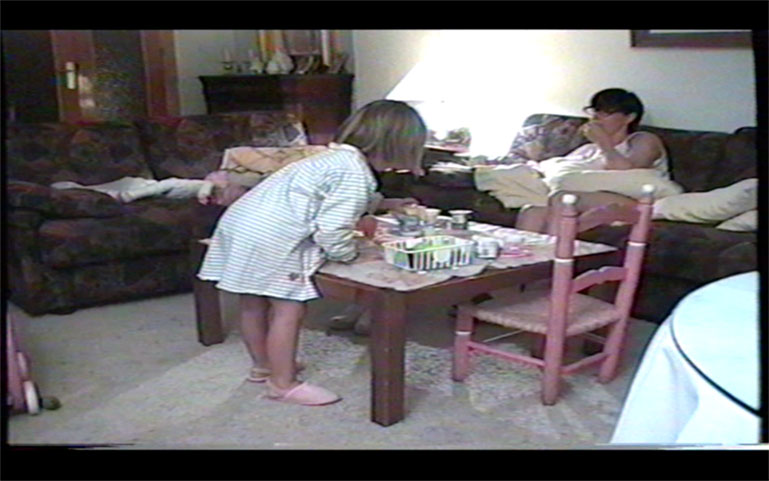

1. TRANSCRIPT: In the living room of a rented flat there is a 5 year-old girl. She is making plastic dinner for her plastic dolls while silently staring at the TV. She needs to hang the clothes out to dry, so she goes inside the kitchen, ties a string across the room, and hangs a kitchen cloth – Souvenir of Firenze – among other items. Her bedroom is filmed via a long, slow pan. On the floor lies a Moroccan kilim bought in the 1980s and brought to Granada by car. On it stands an army of pink teddy bears and blonde dolls, making a circle. They are all female. They are having blue, pink, and yellow plastic Lego for dinner. The crockery is made from disposable green and red plastic plates and cups from the girl’s second birthday - hand washed after the party was over, saved for another time. They are as shiny as the 1990s plastic. Dolls are talking to each other, exchanging their opinions about the artificial fruit and veg that they are eating.

Hours later, the girl’s bedroom/dining room has been transformed into a big, collective pink campsite, so the dolls can sleep. Everything is pink, purple, and white, and they are all together. They sleep on boxes, handkerchiefs, and mats. There is a life-sized bed in the background. The girl is filmed while she is fast asleep. The girl is me. I am exhausted. I have been cooking for hours. I cooked for them. I watched them eat. I watched them talk. I cleared up the table. I hung the laundry. I made them beds. I put them all to bed. It’s 5pm. The girl’s body has hours of hard labour inscribed upon it. She knows, and there she lies – satisfied that there are no intruders in her house.

2. WEDDING

Mother: So where did you leave the groom?

Me: He’s left the wedding already. He got married and just left to get some cake for himself. What nerve!

Mother: So how come you’ve got such a grown up girl if you just got married?

Me: Because she was born in 1950.

Mother: You’ve got a beautiful bouquet.

Me: Yes my boyfriend got these flowers for me so we could get married. Although I bought them myself.

Mother: And did your boyfriend pay?

Me: I didn’t have a dime on me. They cost him 300,000 pesetas.

Mother: Wow! Is that why you got married? Because he’s rich?

Me: I have absolutely no money. He’s got to lend me money all the time so I can pay for stuff.

Mother: Oh, how nice. That’s really nice.

3. ANALYSIS

This archaeology-in-progress is an exercise in rewriting my own ‘herstory’ through reviewing my personal archive and subjective memories. Through the transcription, manipulation, and reassembling of footage recorded by my father that extensively depicts the domestic sceneries of my early childhood in the mid 1990s, my work explores the domestic environment as a political arena.

I argue that ‘domesticities’ - the affective architectures into which we are born and which we constantly inhabit - are devices of explicit cultural politics employed to (re)produce social reality and uphold structures of patriarchal oppression and domination. As such, these structures of power have the capacity to create, to produce, to articulate, and to structure. Yet, they are malleable, and thus subject to intervention and reinvention.

The footage features different everyday domestic scenes - in my family home in Granada, holiday apartments in the area, or the interiors of my relatives’ homes, where festivities are filmed. All of these interiors are perceived by my younger self as paradigmatic architectures that I constantly imitate in my own playground – my parents’ house. In the videos, I perform a series of gendered rituals of caring which mirror the ways in which my own mother takes care of me. In these performative acts, some of them induced, some of them spontaneous, I impersonate stereotypically female characters such as a bride, a nurse, or a princess, simultaneously channelling the ways in which I have been disciplined. I also attempt to rebel against them by asserting my own agency and refusing patriarchal authority.

In the reassembled videos and transcriptions, the adult characters in my childhood appear as political agents in delimiting, shaping, and constraining my gender expression. Through adding my own narration, my father’s gaze is contested and re-appropriated in order to depict a constant struggle in which language, gender, and power are at play in the definition of my own subjectivity. In this contested territory, domesticity plays a central role in the shaping and reclaiming of myself, through the queer hyper-femininity of altered rituals of reproductive labour and performance of typically female roles.

The enclosed, pastel home environment and the poised, often pensive, melancholic adults around me echo a sense of protection, love, confinement, and enclosure. Yet the fascination of my father - an architect himself - with the scenographies he captures, suggests a sense of wonder and curiosity at my own personal development. Through play, my younger self creates a unique, pink universe of plastic food, and a big matriarchy of female characters in which I am my own boss, but which is routinely subject to heteronormative correction. Simultaneously, the aesthetic qualities of hyperfemininity that I stage repetitively create an audio-visual drag narrative of gender resistance, a narrative driven and dominated by the colour pink as the ultimate signifier of femininity.

In order to start producing this piece, I have had to seek collaboration from several members of my family. The very fact that I am turning to this material with a specific ‘archaeological’ purpose has been, at best, met with curiosity, and at worst, with a sense of unease, as if the very act of making ‘private things public’ constituted a sacrilege of some kind. What is, after all, so sacred about a home? What secrets do we want to keep from others? Certainly, the power of disengaging a piece of everyday life from its original space-time context means that it is automatically re-politicised.

In my recent work, I have been using the term ‘domesticities’ to define a particular architectural landscape made of the spatial, emotional, material, economic, sexual, and territorial variables associated to the realm of the home and the everyday. As such, ‘domesticities’ are traditionally associated to the feminine, the reproductive, the secondary, the innocent, or the anecdotal. However, they also constitute an incredibly powerful system that has the potential to shape and maintain the entire configuration of our society. ‘Architectural domesticities' are often overlooked, yet they are key elements in the construction of (gendered) subjectivities, political objectivities, and spatial regimes. The home is still thought of as a familiar, neutral, sunny, and apolitical space - an image chiefly embodied and disseminated through the domestic and town-planning giant IKEA.

Modern domestic spatial regimes possess a quintessentially bio-political nature: they have long been used to administer and regulate human behaviour, making some actions possible and some actions impossible, much in the manner of an ‘operative system’. Domesticity is fully involved in the social machines of identification, exchange, consumption, pleasure, critical expression, and undeniably the construction of social subjectivities and objectivities, informing constructions of identity and belonging, as well as administering the encounter of otherness.

Through re-appropriating, publicising, and reassembling fragments of an environment which is seen as anecdotal, private, and trivial, I seek to reclaim the public and political nature of domesticity whilst queering the masculine-public / feminine-private division which permeates throughout the entire piece. At the centre of this deconstruction sits the logics of ‘feminist economy’ as advocated by Silvia Federici, who argues that not only has domestic work been made invisible, unpaid, cast aside, and used as an oppressive tool against women’s bodies – but that indeed, reproductive labour constitutes the very core of global economy, and should be valued as such.

My father bought our Sony handycam in 1994. By then, the digital recording of everyday life was starting to become a ubiquitous reality for the Western middle classes. The possibility to narrate one’s own life was read in terms of ‘democratisation’. Thanks to the technology behind modern household items, we were not mere consumers of images, but now producers, marching progressively through the media-saturated ‘city of interiors’. With his handycam, my father becomes the silent, reflective, neuter ‘eye’ of the family, at once an outsider and the sole narrator of our story.

Through producing a female gaze which contests, reappropriates, and renarrates my own history as previously told by others, I seek to perform an act of resistance. Twenty-two years later, the child that is portrayed in the film stills declares that she knows she was being watched. She puts her intuitive, spontaneous, dissident behaviour into words and images, and recuperates the agency that was taken away from her. She subverts and reverts the gaze outwards and uses subjectivity as a tactic resistance. This work is also an exploration of autobiographical writing and lived experience as a political tool to relieve trauma and rewrite oneself. Through creating a female gaze that is able to process and reshape this trauma, I aim to create a safe space from which to be able to stand. Building, so to speak, a new architecture of personal freedom and collective caring in which the acts of healing and caring become queer, feminist practices.

Through the female gaze, the home becomes a public space for political resistance, an arena for change, and a historical mirror of the constraints and issues of a generation that encountered heavy gender bias and material abundance growing up – both certainties that are now fully extinct in our lives as adult, queer millennials. Thus, ‘domesticities’ emerge as productive, vibrant arenas of potency in which these disputes come into play. Through the redefinition of domesticities as political practices, societal certainties can be strongly challenged, contested, analysed, and redesigned. In this scenario, ‘re-coded domesticities’ act as tools that can posit ‘the feminised everyday’ as an architectural site of emancipation and contestation, as a radical tool where art and subjectivity occurs, and where new power structures, societal configurations, and revolutionary structures of care may emerge.