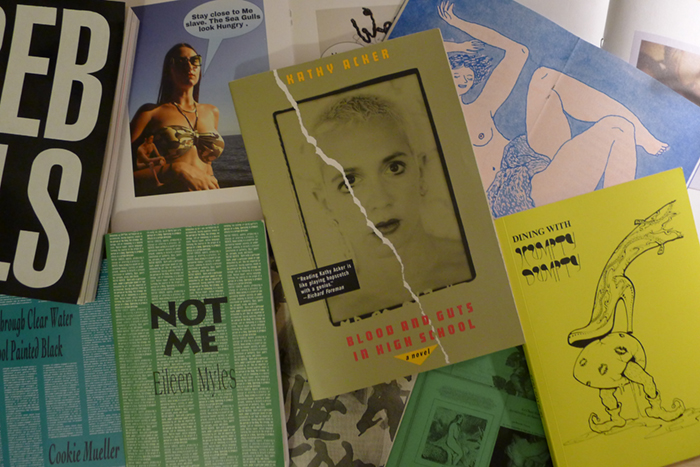

Images courtesy of the author

Sex in America is S&M: Reading Blood and Guts in High School

Aimee Bea Ballinger

Reading Kathy Acker always makes me uncomfortable. I recently re-read her 1984 novel Blood and Guts in High School for the third time and still managed to emerge from it feeling violated and a little out-of-body; like sitting for too long under bright strip lights and slow blinking back into reality. Acker writes so fiercely though her body that it’s impossible not to respond physically: flesh rises into goosebumps, eyes widen, and the throat swallows hard and contracts.

Beneath the heavy handed references to incest and rape slicked across its surface, Blood and Guts in High School can be read as anti-capitalist, and as we know there are few worse places to be under capitalism than the female body. Acker’s vehicle for illustrating female lack and desire is Janey, the novel’s unlikely ten-year-old protagonist. Janey is young, sick and desperately clinging to a crumbling relationship with the provocatively named Father. The dialogue between Janey and Father is tedious, cyclical, humiliating and interspersed with Acker’s graphic, sexual, and oddly beautiful illustrations. One of which features two headless shirted men, their exposed cocks hard, and accompanied by the caption: ‘boyfriend, brother, sister, money, amusement, and father’.

Janey’s tender ten years, the behaviours that belie them and the semantic use of Father are a snarling comment on the entrapment of women under capitalist patriarchy, where they are historically seen as infantile, inferior, insufferable and ignorant. By striking out and gorging on sex, drugs and violence, Janey tirelessly attempts to stuff the void left by a lack of care for her body both in her relationship and in the world generally. Under capitalism in America, women are bound, gagged and reduced to products, branded and disposable. ‘She was a freak and because she couldn’t be anything else and because she wouldn’t be quiet and hide her freakiness like a bloody Kotex.’

It’s near impossible not to empathise with Janey’s physical and emotional ache and chaos. Midway through I get up to take a break from reading, eat an apple, open a window and pace my flat to try and feel more wholesome but nothing settles me. Acker’s language, mutinous and visceral, sears the flesh. I’m reminded of times in my life I’ve stumbled blindly into situations where the Father/Lover dichotomy has spilled and oozed around the edges; where I’ve become devoid of lust; a passive consumer or giver of care that is neither needed nor deserved. Acker’s characters may seem far-fetched, but the shrouded honesty that propels them slides uncomfortably under the skin.

Although not published until 1984, Acker wrote and copyrighted Blood and Guts in High School in the late 1970s. New York’s East Village (in which a section of the book entitled ‘Janey becomes a woman’ takes part) was a place of immense poverty, violence, and corruption. Despite the overspill of junkies, pimps and hookers that inhabit the barely fictional streets in Janey’s neighbourhood, the true source of its corruption is the white men in suits and cassocks who treated the redevelopment of the city as an opportunity to spawn their own brand of ethnic cleansing.

‘One of the landlords burned down his building so he could collect insurance money. Two families and one pimp were sleeping in this building when it burned down. The landlord sold the charred lot for lot’s of money to McDonald’s, a multinational fast food concern. This is how poor people become hamburger meat.’

It’s in these passages that I soften to Acker, her prose chewed up and spat out as it screams with a tenacious anger that leaves tinnitus ringing for days. New York in the late 1970s was a place of outstanding inequality, ravaged by debt, and a Republican government hell bent on auctioning off the city. Entire neighbourhoods were left to fester and communities to rot, and within them young gay men were dying in droves from a disease that still had no fixed name, let alone a tangible cure.

In a country ruled by a systemic violence, neglect, and abuse of power, bad taste by contrast seems revolutionary. A queer woman writing forcefully through the sexualised body invites censorship and flicks a giant fuck you to the dictators of good taste and acceptable form and language. Acker’s refusal to adhere to traditional narrative structures, spinning instead into dream maps, commandeering whole pages for portraits of genitalia, senseless scrawls, and frustratingly clunky dialogue causes the reader to feel confused, isolated and attacked along with the subject. Blood and Guts in High School is corporeal in its expression of anger and isolation. The body more than anything cannot be silenced. The body continues to exist despite the most violent efforts to extinguish it: even after death it haunts with its stink.

Reading Kathy Acker is like holding a giant gobstopper in your mouth. The lips distort, jaw aches, saliva glands over-activate and you start to gag a little. Her writing can feel unfriendly, overbearing and at times inaccessible, but for me it’s worth the stretch precisely because Acker was a woman unafraid of appearing unfriendly, overbearing or inaccessible. Rebellion is only ugly in the eyes of those you are rebelling against; and for Acker, writing the antithesis to the status quo—the pissing, shitting, fucking, screaming female body—is the ugliest of them all. This is why I continue to return to Kathy Acker; as a reader and a bookseller, I am drawn to books that irritate in the same measure that they educate. Books that continue to scream long after you close them. I don’t think that reading in itself can be a radical act but to an extent writing can, and Kathy Acker even in death continues to be a relevant, transgressive and radical voice.