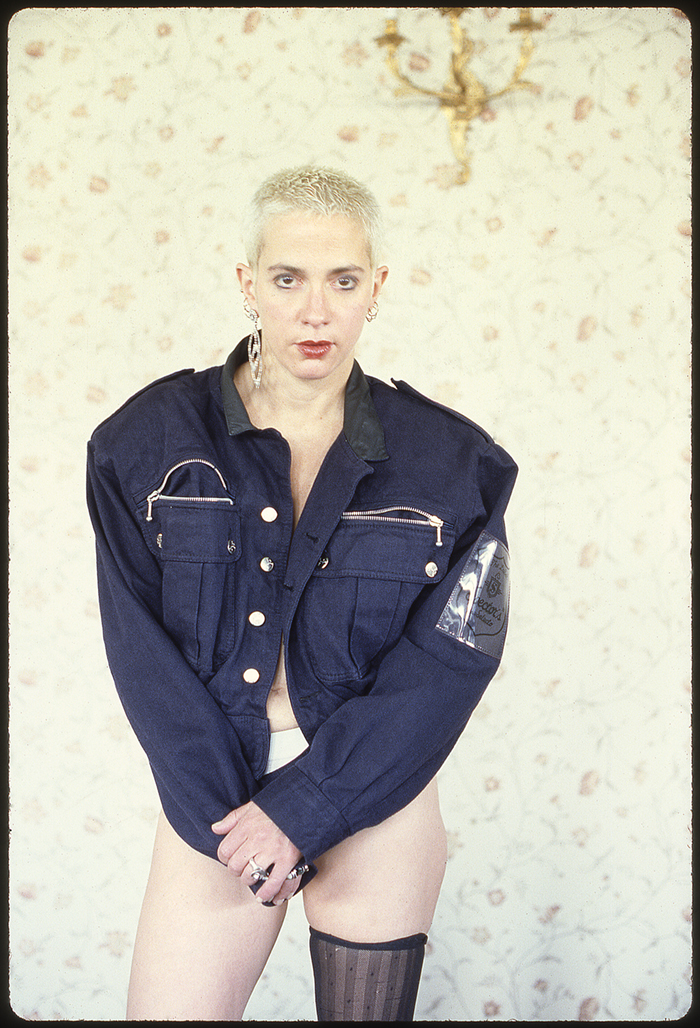

Kathy Acker at the Gramercy Park Hotel, New York, 1998. Photo courtesy of Michel Delsol © Michel Delsol.

Book cover courtesy of Penguin Books.

Chris Kraus, photo by Carissa Gallo, courtesy of Penguin Books.

A New Cuntology: Chris Kraus on Kathy Acker

Octavia Bright

A self-described ‘myth-maker for digital flesh’, perhaps Kathy Acker came too soon. I can’t help but think what she would have made of the cultural collage of contemporary social media: machines for personal myth-making and visual theft that encourage us all to be the architects of our own image. As told by Chris Kraus, the rise and fall of Acker the picaresque heroine – for whom sex was an engine and a refuge, and the body as much a tool for writing as the pen or the mind – feels like a retrospective fable delivered via the life story of a force of nature who somehow still exists outside of chronological time.

Fascinated by sex and power, Acker’s body of work strong-arms Great Artists into metaphorically fucking one another on the plane of her own writing, creating bastard theoretical children of the kind Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari celebrate. Ultimately, these mangled narratives act in the service of understanding herself: spinning her own literary history across centuries with appropriated fragments and references, Acker was an artist constructing her own canon while simultaneously exploding it, the punk outsider that nevertheless wanted to be recognised by the culture she appeared to hold in contempt.

Kraus effectively marries the kinetic energy of Acker’s work with that of her life, presenting her as a woman constantly in motion physically, narratively, and emotionally. Acker famously compulsively revisited her origin stories creating a constantly evolving personal mythology, the motion of which was reflected in her restless lifestyle, mostly conducted at the fever pitch of a Greek tragedy. Combining meticulous research with the flexibility of Acker’s own self-creation, Kraus’ portrait exploits the tension between movement and stasis made possible by a book length tribute, at once pinning down its enigmatic protagonist and giving her space to roam through its pages.

To know Acker through her own writing is to understand her as an unscrupulous ratbag swinging through life in a fury of acting out, seduction, hunger, and storytelling. She endorsed the pursuit of sex, BDSM, and intimacy as paths to the unconscious and escapes from repressive social norms. To know her through Kraus’ writing is to zoom out. In her role as biographer, Kraus weaves confidently through fragments of Acker’s work, diaries, myths, and recollections. She stages a drama populated by a pornucopia of players, including those who loved Acker, were frustrated by her, used by her, and those that used her in return. As protagonist, Acker appears on an emotional high speed chase where the finish line is not the point and the other driver is the disappointing limitations of her own humanity: ‘being human is too boring and difficult,’ writes Acker, ‘who wants to be human all the time. I’m sick of being rational and doing things I’m becoming a cat.’ Kraus’ portrait is driven by this ever-frustrating conflict.

The book has one leg slung over the gate that separates academic work from more mainstream biography – after an extensive list of sources and a fulsome index, Kraus lists in the acknowledgements a number of researchers and librarians who helped her, but also includes a tarot reader and astrological adviser. Stylistically, Kraus plays straight woman to Acker’s anarchist, gently but firmly corralling information in order to chart the pleasures and perils of the art of becoming – an ontology of becoming artist, becoming Acker, becoming biographer (‘on what may or may not be a biography of Kathy Acker’), continuing the construction of an intellectual history of women who self-determine in prose.

At the heart of this becoming is desire itself, something we can all relate to whether or not we buy into Acker as the counter-cultural anti-heroine. But I imagine this is precisely one of the things that will turn certain people off this book – the raw vulnerability Kraus draws out exposes a fundamental part of the human emotional experience: the desire to be seen, wanted, validated. Sure, we don’t all choose to do that at the outer limits of experience like Acker, but the nakedness of her need is confronting because it is relatable. Her work unlocks primitive emotion in readers because while formally considered it remains unguarded in its motives and discoveries. The Acker that Kraus presents us with is at times a machine for whom everything is desire and praxis, but at other times teeters on an awakening, constantly treading the threshold of her own sovereignty.

Is it only through Kraus’ eyes that Acker becomes more than a post-punk enfant terrible? Other reviews comment on the author’s ‘sympathetic’ perspective. For me, the strength of this work is that it finally provides Acker with a female interlocutor. Throughout her career, Acker’s projects were for the most part motivated by a movement towards or against a (physical or psycho-) sexual relationship with a man she admired or wanted to possess, as though she needed to subsume each of them and what they might offer her in order to continue becoming herself. Similarly, in Kraus’ breakthrough book I Love Dick (1997) it is the presence of a male interlocutor (or two) that draws out her desire. But here, Kraus and Acker meet artist to artist, in a relationship fuelled not by desire but by respect.

Biography plays a powerful role in the upholding of a myth or cult of personality, and is a statement of consolidation of status, which serves to legitimise an artist and their work. At one point, Kraus references Sylvère Lotringer’s description of myth as a ‘powerful emotional bond’, and in writing this book, she unarguably traces a potent bond between herself and her subject. Susan Sontag stated that real art makes us nervous, and that one tames works of art by reducing them to content that can then be interpreted. Although there are some who would argue that Acker’s work is not ‘real art’, what is important here is that Kraus does not try to tame Acker. This book is not about seeking validation – both women are polarising figures in their work. In fact, potential parallels between the two writer/artists delayed Kraus from starting the project for many years. When I interviewed Kraus eighteen months ago she was working on the book, and she explained she had been especially struck by the tragedy of Acker’s lonely death, so shortly after the publication of I Love Dick, had begun speaking to people who had been close to Acker with a mind to writing her story. She found, however, that even though her own writing feels to her – and me – to be very different, she was being toted as Acker’s literary successor, so she put the project aside for fifteen years, perhaps until the risk of becoming completely subsumed by her subject felt less acute.

In some ways, Kraus’ book flies free from Acker’s work as a provocative tale about the nature and status of artistic identity and how to spin/live it. Acker decried how the media fetishized what she did, and Kraus certainly does not continue in that vein. In fact, in going behind the façade of Acker the post-punk legend the fetish is unravelled, and what is revealed is a person with admirable drive and discipline, self-belief and self-determination, which is inspiring regardless of what you might think of her work. But Acker remains an emblem of how the self-mythologised artist cannot win, how it’s a status that must by default eat itself. The creation of The Great Artist is an oscillation between internal process and the motion of an industry with external players that are a constant necessity – and so, the image is created in motion, fundamentally unstable as the demands upon it shift.

Acker was fascinated by how close it is possible to get to someone (the subject of her infamous project with Alan Sondheim, The Blue Tape, 1974), and perhaps the answer to this question is: write their biography. Does Kraus become Acker? Do we become Kraus? As we slip between the subjectivities of both writers, our understanding of multiple texts evolves, and Kraus conjures Acker so vividly that the experience of reading this book is like spending time in the company of both women, a triangulation of all three of our subjectivities somehow: we become a dialogue of three, a trio of voices, experiences, ambitions, desires.

As Kraus notes, ‘like most human communication, Acker’s account of her life fluctuates between rigorous honesty and self-serving white lies’, a statement classic of the empathetic wisdom she brings to the project, and one we might extend to the art of the biography itself – there will always be something in it for the writer, as well as the subject. But perhaps the self-serving element here is the creation of a kind of ‘trialogue’, a pan-temporal séance between Acker as conjoured by Kraus, Kraus herself, and the reader. The book ends with words from artist Martha Rosler, who, in conversation about Acker with Kraus, remarked that they – the implication being, women artists – are ‘all the same in a way’, that she could have been Kathy, Kathy could have been her. And so, Acker’s drive to possess (and ingest) men is reframed as a possession of a different sort – a hauntological lineage reframed in the feminine, a cuntology, where each becomes the other not in an act of competitive domination but one of identification and radical empathy.