Anna Ray, Margate Knot, 2016. Cotton, polyester, machine and hand stitch. Courtesy Anna Ray.

Hannah Ryggen, 6th Oktober, 1942, 1943. Tapestry. Courtesy Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustri–Museum. © DACS 2016.

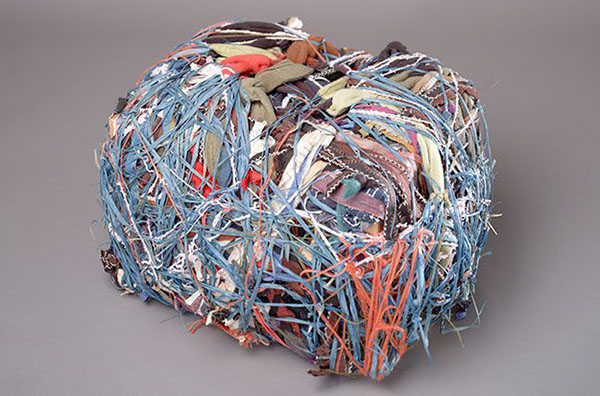

Judith Scott, assemblage de fils de laine, de tissus sur ubne boite de carton, 2003. Sculpture. Courtesy Collection de L'art Brut Lausanne, Suisse.

Louise Bourgeois, HAND, 2001. Fabric, wood, glass and steel. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Cheim & Read. Photo: Christopher Burke, © The Easton Foundation/ VAGA, New York/DACS, London 2016.

‘Out flew the web and floated wide’: Entangled: Threads and Making at the Turner Contemporary

George Mind

Weaving is enshrined in myth and the literary canon as both an emblem of woman’s oppression and her rebellion. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the defiant Philomela is raped by her brother-in-law, Tereus. When she threatens to speak of his crime, he cuts out her tongue. Overcoming her muteness and determined to bring her attacker to justice, Philomela weaves a tapestry illustrating the assault, sending it to her sister Procne, who carries out a grisly act of revenge on Tereus.

Another mythic weaver, Penelope, was painted by John William Waterhouse in 1912. Penelope is told she must remarry, for her husband Odysseus is deemed lost to the Trojan War. Taking control of her future, Penelope insists she is weaving a burial shroud for her husband’s father and will remarry when it is finished. Every night until Odysseus’ safe return Penelope unpicks her work at the loom. Waterhouse depicts Penelope biting off the yarn, drawing it back as if it were an arrow, absorbed in her work. Aloof, she ignores the pining, pathetic suitors’ offerings.

In Alfred Lord Tennyson’s much-loved poem ‘The Lady of Shalott’ (1833), an imprisoned maiden is obliged to weave “a magic web with colours gay”, looking at the “shadows of the world” obliquely, through a mirror, or else a curse will come upon her. Yet when Sir Lancelot rides through Camelot the lady asserts her desire, fearlessly turning away from the mirror to gaze upon him from the window. In the Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt’s depiction of the poem, we encounter the statuesque lady twirling in a frenzied dance, her back arched like a cat, in the moment when she breaks the spell and “out flew the web and floated wide”. She is depicted ensnared by threads, yet also commanding them. The painting’s vivid hues quiver under the lady’s bewitching gaze, her awakened sexuality symbolised in the swirling, thread-like coils of her hair… “I am half sick of shadows, said the Lady of Shalott”.

For centuries, weaving, mending and embroidering the family’s cloth were a part of everyday, domestic labour for lower class women. For upper class and noble women embroidery was deemed a suitable pastime, something that could easily be picked up and put down to pander to the needs of any man or child that came into her orbit. Yet, looking back, many self-identifying women artists have reclaimed this heritage, working threads and yarns into seminal works of art. The Turner Contemporary’s current exhibition, Entangled: Threads and Making, embraces this knotty history, bringing together forty women artists from around the world, situating contemporary artists alongside their foremothers.

In the elevator up to the exhibition a kaleidoscopic yoghurt-smeared carpet lines the walls, smothering visitors in its acrid odour as they ascend. Samara Scott’s gloriously abject work Old Lake (2016) revels in the grottiness and exuberance of Margate, referencing the delirious patterns of arcade carpets designed to keep gamblers awake. Another piece responding to the immediate landscape and community around the Turner Contemporary is Anna Ray’s cooperatively produced fabric sculpture, Margate Knot, commissioned for this exhibition. The sculpture, installed in the exhibition foyer, references Margate’s heritage and celebrates a community of makers: the local women who responded to a callout by Ray, and produced each fabric element as a team. Margate Knot foregrounds the active term ‘making’ of the exhibition’s subtitle; this is a generative work that has created jobs in Margate, giving many women the means and confidence to keep making.

Once inside the exhibition space, the show pivots around a potent symbol of making: the outstretched palm of Louise Bourgeois’ blood red Hand (2001), threadbare as if flayed or raw from working; it appears to be unfurling from a tight fist. The hand arches upward, guiding our eyes to a Judith Scott sculpture, suspended from the ceiling. Bourgeois’ family owned a tapestry restoration workshop and as a child she would assist her parents, delighting in the work of reparation. Throughout her career, Bourgeois made many sculptural, textile artworks, returning loyally to her beloved motif of the female spider, spinning her web and cannibalising courting males. In an astute curatorial decision, Karen Wright chose to display Bourgeois’ work alongside that of Judith Scott, an artist who would bind found objects in pieces of thread she had gleaned from her surroundings, just as spiders catch their prey in a web, wrapping it in threads of silk.

Scott’s tangled sculptures are totemic, magical objects, with the feel of protective talismans, yet their repetitious binding also speaks of frustration and entrapment, perhaps reflecting Scott’s feelings towards being institutionalised for most of her life. Many works in the exhibition tease out issues of vulnerability and strength, personally and politically. Delicate works, such a column made of horse hair strands, appear guarded by large-scale, defiant political statements such as Hannah Ryggen’s anti-fascist tapestry 6 Oktober, 1942, undoubtedly the masterpiece of this show.

Entangled triumphs in exploring thread and fabric as metaphors. Unravelling, for example, is registered in works such as Loosening Fabric #6 (2017) by Aiko Tezuka, an artist who unpicks fabric with a team of assistants, creating intricate sculptural pieces. Maria Roosen’s When I think of you (1998), is a piece about sewing oneself back together in the aftermath of trauma. Roosen produced this embroidered work following the death of her partner, sewing lines methodically to cope with grief. In the work’s accompanying text, Roosen explains that with the line, “you know where to begin, and where to end.” Yet Entangled keeps the poignant and the playful in balance, featuring alongside the more emotionally taxing works, gentle, drooping, knitted phalluses and invitingly yonic, natural-fibre sleeves that hang from the ceiling, accommodating the head of many a visitor.

The exhibition’s momentous achievement is its radical expansion of what we understand by ‘textile art’; the artists of Entangled take this mode of artistic production into new realms entirely. At a round table event bringing the artists of the show into discussion with the curator, Karen Wright, a contentious question was raised: are there inherent, detectable qualities to women’s art? This question agitates the essentialist, somewhat retrogressive sentiments of second-wave feminism that we have worked so hard to revise. Yet the resounding answer was that yes, there often is something particular to women’s art: a type of creativity born out of limitation and requiring resourcefulness. Entangled reveals the many ways in which women artists have used ‘domestic’ and ‘waste’ materials – from carpet fluffing tools to animal hair – to tell stories about their lives and campaign for change. This is a show with boundless ingenuity, vivacity and assertion, a show by women artists who, like the Lady of Shalott, are half sick of shadows.