All images courtesy of Annea Lockwood.

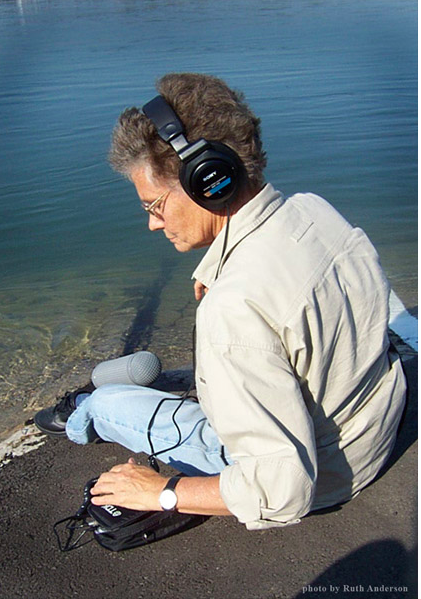

Ear-Walking Woman: An Interview With Annea Lockwood

Louisa Lee

Annea Lockwood is a sound artist and composer who has collaborated with sound poets, choreographers and visual artists since the 1960s and was one of the few women artists working in experimental music in a period where this field was still dominated by men. Lockwood’s work has been shown more recently at Flat Time House in London and was featured in the publication Pink Noises: Women on Electronic Music and Sound (2010). Louisa Lee is a collaborative PhD candidate at the University of York and the Tate working on the project, ‘Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-79’. As male artists largely dominated conceptual art in the period that she is researching, she has actively pursued histories of female artists working at the same time and is particularly interested in women who make experimental music. The interview was conducted over Skype as Annea is based in Upstate New York and Louisa is based in London.

Louisa Lee: I’ve found it quite hard to find out about women working not only in conceptual art but also specifically in experimental music. I was wondering if you could tell me more about that.

Annea Lockwood: There are good reasons why the second wave of feminism arose during that period and why it was really vital to a lot of women artists. It was a very male dominated period. When I look back over programs I have from my time in England, particularly looking at the programme catalogue of the ICES festival from 1972 that did attempt to assemble everyone working in experimental music at the time, there are extremely few women in the ICES catalogue. By extremely few, I mean four or five. One of which was Charlotte Moorman and myself and the others were pretty much working in groups rather than presenting work individually. In general, when looking through other programmes, I don’t see any women. The situation for women was one of continuing subordination. Women artists often played a supporting role. I’m thinking of the artist Jennifer Pike who married Bob Cobbing who's been doing beautiful and important work all her life. She’s better recognised now but she is better recognised because of the efforts of women and the women at Flat Time House, bringing her into the foreground. She was much less prominent at the time; although Bob never saw her this way, other people did. I remember sitting in a group of people my age when I was in my mid-twenties, working on strategies for marches and protests against the Vietnamese War, and it was so obvious that we were there to make spaghetti and do the housing arrangements. But, it wasn’t all bad and those of us who were working at the time did manage to carve out a creative space for ourselves. It was an exhilarating space. There was another woman who was married to John Latham, an excellent artist in her own right, have you come across Barbara Steveni?

LL: I have actually because I’ve been doing a reading group at Flat Time House about women artists in the sixties and seventies. I haven’t met her but I know of her.

AL: She would be a tremendous source of information I would suspect and her own work is really beautiful and interesting.

LL: I came across your work initially because I went to a talk by Frances Morgan and Nina Power from The Wire and they were talking about women working in experimental music. I understand that you were friends with Bob Cobbing and that might have led to your involvement in the Destruction in Art Symposium (1966) but I’m interested to know if there were other women involved in the Symposium?

AL: Other people have asked me about DIAS and I have very few memories of it, which means I wasn’t very deeply involved. Bob and I did a workshop at DIAS in which we were collecting vocal sounds from people and we assembled those sounds at that time and presented them in some way at a small festival called Pavilions in the Park on the Chelsea Embankment. I remember writing a sort of manifesto about music and sound and destruction in art, and I recall I got involved in one of Ralph Ortiz’s piano destructions. At the time I’d been making a sort of permanently prepared piano for a couple of years thinking John Cage never had that freedom so I’d take it and then Ralph got me involved in one of the piano destructions. I really wasn’t very interested in destroying pianos, there were other things I wanted to do. I was certainly around for the events of DIAS but I don’t remember being anymore deeply involved than that.

LL: Could you tell me more generally about women making experimental music at the time? What led you into that world, which allowed for a feminine voice? Was there a network at the time?

AL: No, I didn’t have a feeling of a female network in London at the time. Pauline Oliveros and I got in touch in what must have been the early seventies, through Source magazine and through Charles Amirkhanian - a composer who thought we should be in touch. We started writing to one another and we started doing Pauline’s ‘Sonic Meditations’. She started presenting some of my work over in San Diego, so it was through Pauline and through the American experimental musicians who started coming through London all the time that I started making friendships with the American experimental music circles, which were very hospitable when I moved to the States and have been my community ever since, but in London itself, I didn’t have a sense of a female network. It is really lovely to see that those networks are operating now. My network was really the group around Hugh Davies, who was a really good friend, and Bob, and the sound poetry circles but that was working with men and I really don’t recall women making experimental music at the time, not English women. I mean obviously Yoko turned up at some point and Carolee Schneemann. Carolee worked with sound at some point. Charlotte Moorman too, who needed to come out from behind the shadow of Nam June Paik. Women were always in the shadows. One of the things that I think made the States seem so magnetic for me, other than the music being so fascinating, was the involvement of strong women artists in the experimental scene. Once I moved to the States I stated collaborating with Alison Knowles, I worked with Marilyn Wood – a choreographer and sometimes Ruth Anderson and I collaborated so it shifted. It was wonderful and invigorating.

LL: It sounds like America was much more hospitable for women than Britain. What were the available platforms for you to perform or distribute your music? Was it easy for you to get your music out there? Or was that not the point?

AL: It was very different, very informal. If you weren’t involved in the contemporary classical music scene then it was very informal. I would have concerts promoted on the Society for the Promotion of New Music, which was strictly music, but I would also be invited by Wendy Harp and Bill Harp in Liverpool to come and create and present work there. Tiger Balm (1970), for example was done at a little theatre in North London. Initially it wasn’t a dance it was a theatre piece and I did performances and presented work. I presented at the ICA once or twice and travelled around with Bob for a couple of years doing festivals and readings. The experimental scene was not as laid back in terms of venues as the one I later found in the States, but it was moving towards that. It was a matter of making work and presenting it to the community and getting feedback. Distribution of work as product was not in the air as it is much more so now.

LL: Do you feel you need to take distribution into consideration now, or do you still work in a way that still follows the old model?

AL: I have pieces that can be recorded and they are done that way so they have an afterlife. I’m happy that my scored works are going to be distributed finally but I haven’t been very active in this. It may be that I have no training in this. Partly because I grew up in New Zealand where it was a high priority that women be modest, or it was a cultural priority, and the years in London didn’t give me any training in promoting my work and I cant put my finger on why, it didn’t seem to be part of my circle.

LL: How does your work compare now to then? Which projects have you continued and have evolved with you over the years?

AL: My fascination with environmental sounds just continues to get stronger and stronger, and goes back a long way. My work with rivers for instance, I remember starting a river archive in about 1967 and I started getting friends who were travelling to record the rivers and creeks that they came across if they wanted to. Pauline did, and Carolee did, and various other people did, so I started to make an archive of the world’s rivers and streams, which was obviously impossible, but that was part of the point. It was also to focus people on water sounds and their environments. So that started back then and continues. My recent work is probably grounded in a work from 1975 called World Rhythms that I performed at The Kitchen in New York and various other places. It was an assembled live improvisation that used the recorded sounds of volcanoes and tree frogs and various other phenomena. Most recently, I did the work Wild Energy (2014), a collaboration with Bob Bielecki, which takes that further, so we used atmospheric sounds and sounds from vents in the seabeds, and solar emissions, which has been thrilling. I’m now focusing on plant. So that’s been a long preoccupation or interest but at the moment I’m not making instrumental or vocal work. The thread of environmental sounds and concern for the environment continues. I’m a New Zealander.

LL: And now you’re in Upstate New York and still within nature?

AL: Yes, enough so. This morning I made a cup of coffee and went down to the bottom of the garden and sat in my hammock and listened to the birds’ sounds.

LL: As a final note, is there any advice you’d give to younger women making experimental music now?

AL: One guideline I followed for a long time was to always work on your most extreme ideas. I have no guideline in terms of career because people are very savvy about that now but it’s very liberating and fun to work on the most extreme ideas you can come up with and work them out and see where that takes you.

LL: Thank you so much.

AL: Not at all. I’m glad you and others are studying women’s activity in the arts in that period. It’s very good to bring that up to the surface, so thank you for doing that.