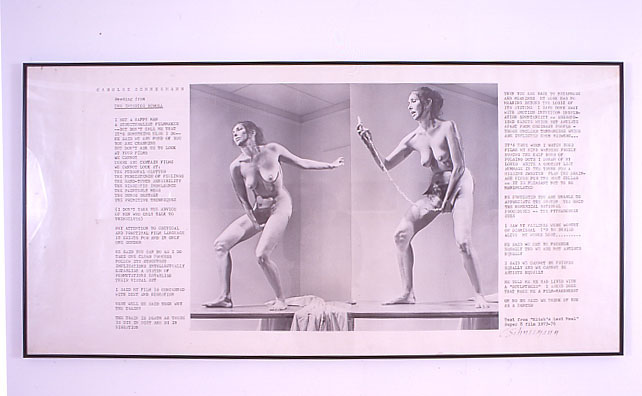

Carolee Schneemann, Interior Scroll, 1975. Photo collage with text. Image courtesy of the artist.

Carolee Schneemann, Fuses, 1967, 16mm color, silent, 18 minutes. Image courtesy of the artist.

Faith Holland, Lick Suck Screen, 2014. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Gendered Embodiment in Internet Culture: The Practice of Women Internet Artists in Twenty-First Century Patriarchy

Jeanette Bisschops

Since the start of the women’s liberation movement some fifty years ago, there has been significant change in the representation of women, yet many things have stayed much the same. Consequently, it isn’t surprising that the discussion of feminism and feminist practice, has been on the rise again in the last few years – both inside and outside of the art world. While feminist artists in the seventies were greatly energised by the emergence of performance and video art, nowadays, the democratizing force for feminist artists is unmistakably the Internet. The motivations for choosing these fields of work or medium are similar: both then and now it has been the new technologies that have offered the most freedom from contemporary male-dominated mediums.

Early feminist artistic critique on the representation of women was part of a general growing protest for equal political, economic, social and personal rights. Coinciding with technological developments such as the introduction of the portable video camera in 1965, these artists were provided with new tools to respond in a personal way to the traditionally idealised, aestheticized and passive portrayal of women in the media and the arts. In the sixties and seventies, the growing presence of media showed a continuation of the female ideal that had dominated the Western art canon, as created by men. For centuries, the art world had been obsessed with the female nude, yet continued to marginalise or ignore the real lived experience of these female bodies. Performance and video artists, such as Ana Mendieta, VALIE EXPORT and Carolee Schneemann, introduced a more intimate and realistic narrative to fight the abstraction that had fallen upon the female body.

Carolee Schneemann’s performance Interior Scroll is a strong example. It was first performed during ‘Women Here and Now’, an exhibition of paintings accompanied by a series of performances, in East Hampton, New York in August 1975. In front of an audience, she began to read a scroll which she pulled out from her vagina, an act that confronted her viewers with their position of passive voyeurs, while simultaneously criticising the abstraction of the female body and its loss of meaning in Western civilization. To put this into perspective, this was only a few years after the abandonment of the Hays Code. This code was put in place in 1930; ordaining that sex could only be implied and never depicted in Hollywood movies. Yet it was also a time when pornographic films were already broadly available. The mainstream porn industry was dominated by male producers, which ensured the dominant representation of sex was from a heterosexual male point of view. Schneemann had responded to the unemotional quality of the available pornography in an earlier film, titled Fuses (1965). The film shows Schneemann making love with her partner James Tenney, as if being observed by their cat. The only actual participants were Schneemann herself, her partner, and their cat. No cameraman. Through this way of filming she became filmmaker as well as the film’s subject, and was thus able to re-create the intimate experience of lovemaking without the objectification of either body. The addition of distortions, through staining and painting directly on the film, relinquished any of the fetishisation of the female normally seen in porn. While Fuses did not follow the code of conventional porn (long body shots of a sex act often ending in the ejaculation of the man) it was labelled pornographic in the art world, leading to censorship and also the frustration of an audience that had expected the usual, tired porn narrative.

Some fifty years later we are living in a world that is even more deeply engrained with media and technology, and we have seen a rise in the (re)sexualisation of women. The early Internet days briefly gave us a promise of an active, inclusive and utopian community. People would be able to leave behind all aspects of themselves that had made it difficult to connect to others in the offline world, such as physical appearance or locations, and form new bonds in a non-hierarchical place where everyone was equal. The Internet would blur all boundaries, including gender boundaries. Unfortunately, we now know that we were not able to leave behind the physical world, especially its cis white patriarchal power system. Our online environment is engrained with objectifying content and sexual violence towards women. Advertisements, the driving force of many sites, still show the age-old trend of women’s bodies being used to sell products. Additionally, recent research by The Guardian showed that female journalists as well as ethnic and religious minorities have to deal with a continuous flow of aggressive responses to their articles, something that almost every woman who has posted her opinion online will be familiar with. Online porn has become a huge commodity, and again the content of porn sites are created mostly for the straight male gaze, rarely accommodating the sexual desire of women themselves. A large amount of (free) porn is consumed by a high percentage of Internet users, often from an incredibly young age. These statistics, joined together with the media and contemporary culture’s objectification of women, does not paint the picture of a world that Schneemann strove for.

Despite all of this, online platforms have not lost all their democratic power, mainly thanks to social media. Expressions or performances of identity in the offline and online world are becoming equally part of ‘real life’. Women, people of colour and LGBTQI individuals are fighting back by producing their own imagery and distributing it widely. And that is exactly what a certain group of contemporary feminist artists are also doing. The rise of activist female net artists is not surprising - now an important part of our social interaction is taking place online rather than in public space. By placing their work directly within popular culture as opposed to the white cube of the art world, they are choosing an even more divergent approach than performance artists did in the seventies. At first, the video work Lick Suck Screen (2014), which Faith Holland placed on the porn site Redtube, suggested the performance of a blowjob, but disrupted the viewers’ expectations by ending with Holland repeatedly licking the lens of the camera. By posting her video on a widely used porn site, she was able to intervene directly at the source. Her anticlimactic video disrupted the flow of homogenic porn that is found online, aiming to create more awareness about the viewer’s pornographic and sexual expectations. Moreover, the work elucidates the inability of the patriarchal, white supremacist system to exploit a body that is obscured. Contemporaries of Holland, such as Ann Hirsch, show a similar humorous and self-deprecating way of working, as can be seen in her YouTube video series Scandalishious (2008-2010).

The disruption of expectations achieved by Holland and Hirsch is often far more obscure in work by others. Coined ‘Hot Girl Art’, several (white) female artists have been creating work that they define as a forceful commentary on aestheticized selfie culture, however it is often indistinguishable from the acts they call attention to. While placing feminist artistic critique in popular culture does allow for a bigger reach in non-art audience, it also comes with its own limitations. If an artist wants their work or content to be liked and shared, it often needs to meet the narrow aesthetic standards that it is attempting to criticise. Other problems can occur when one deviates from them. For example, social media platforms have strict rules on nudity that allow them to censor certain content. These rules seem to restrict female self-expression disproportionately, as the ban on female but not male nipples reveals. This creates a catch-22 for many artists. The written and unwritten rules of social media also pose even more barriers for black, LGBTQI and disabled bodies who are hardly visible at all. As Rhizome’s net art curator Aria Dean points out in her essay Closing the Loop: “white feminist artists are the ones with the most traction, yet they still place their work in a racist, classicist and capitalist framework. As a consequence, they fail all types of feminism that are excluded by said framework.” Hannah Black, writer and artist, is well known for exploring the colonial gaze, and often finds herself as the only or one of the few non-white artists included in (online) exhibitions and articles on net art. As Dean remarks, Black’s work is more anti-representative, as she chooses to not use any imagery of herself. This shows clearly in her video My Bodies (2014). Here the first part shows images of white men overlaid with voices of mainly African American musicians singing “my body”, while the second part deals with the concept of afterlife by asking if you would have the chance to come back in any type of body, would you choose to have the same body or not?

As online behaviour and big data increasingly rules our on and offline behaviour and politic, artists might indeed be wise to look at new ways to change this repressive system. Trying to change the system from within may not cut it anymore. As Dean states, “we must devise a new politic of looking and being looked at”. Artists may have to dismantle the system altogether by refusing to play by the rules, as some of the aforementioned artists are already doing. Some feminist artists will have to look beyond their whiteness and sexual stereotypes to be able to join forces and increase the traction that is needed to achieve this.