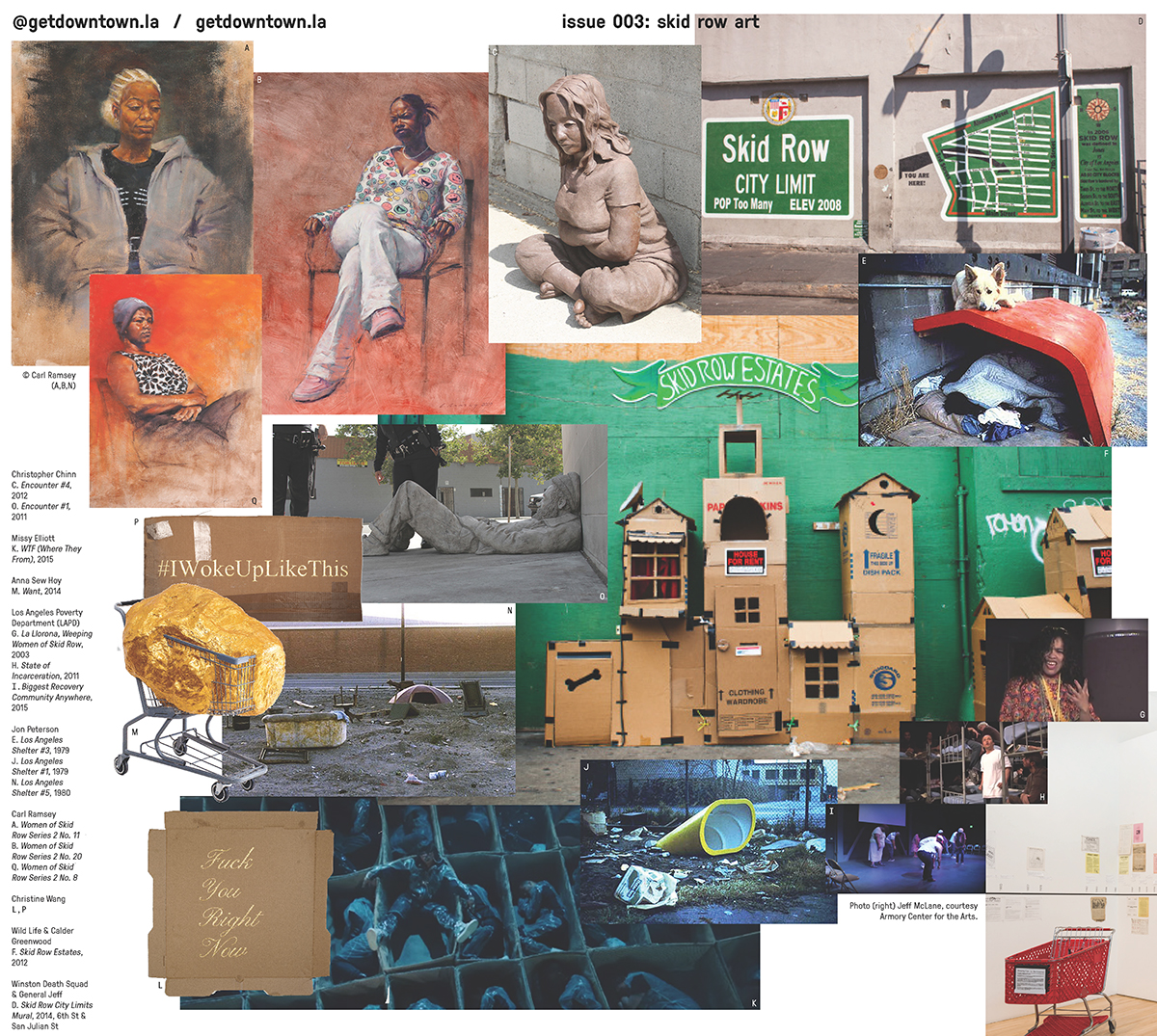

Get Down Town Issue 003: Skid Row Art. Image courtesy of Get Down Town.

Photograph of art by Skid Robot, by Wendy Chavez. Image courtesy of Get Down Town.

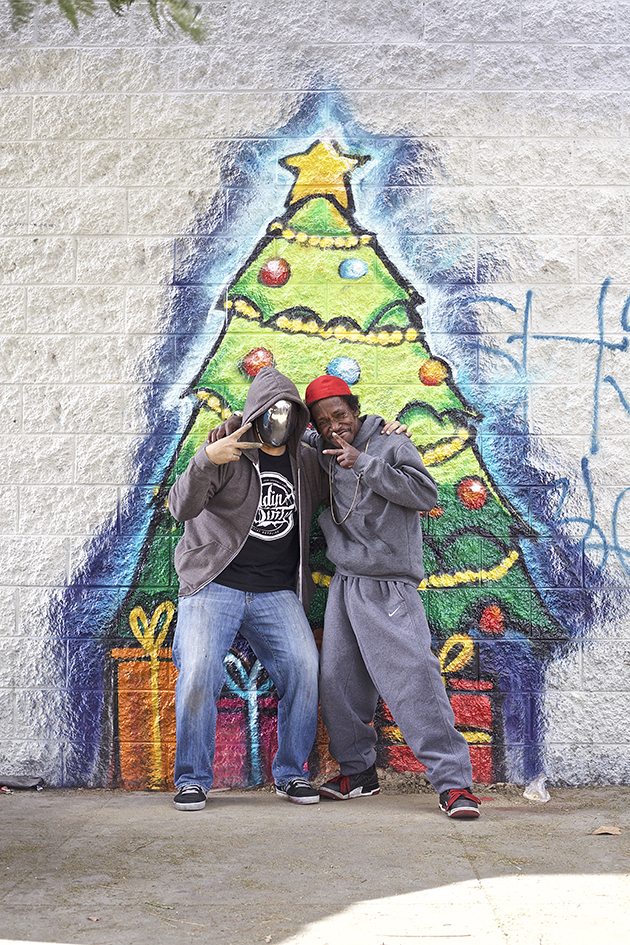

Photograph of Ronald Troy Collins and art by Skid Robot, by Wendy Chavez. Image courtesy of Get Down Town.

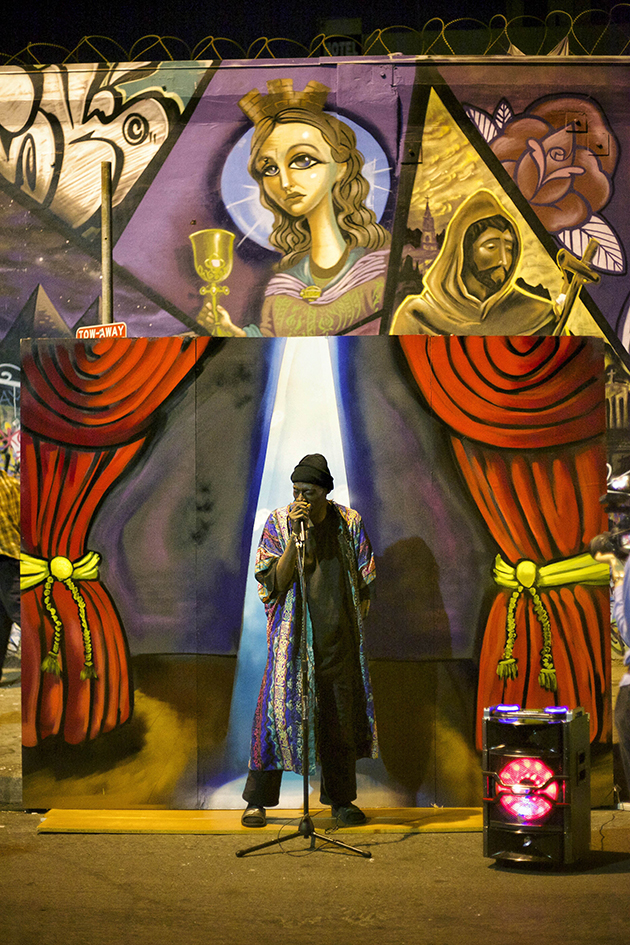

Photograph of art by Skid Robot, by Wendy Chavez. Image courtesy of Get Down Town.

Get Down Town on art in Skid Row

Hyunjee Nicole Kim

In “The Sabotage of Rent” Matteo Pasquinelli notes that, “a purely imaginary fabrication of value is a key component of both financial games and gentrification processes.” Are homeless and drug-addled bodies producing the kind of value that real estate developers care to cash in on? Likely no. I am reporting from the front lines of an expanding Los Angeles, where Google and BuzzFeed have offices in Venice Beach, “Brooklyn-style” loft living is advertised on Craigslist, and signs that read “Make Apps Not War” are pasted on telephone poles and crumbling cement walls. We want artistic innovation and the proliferation of a creative class. We want third-wave coffee shops and Swiss mega-galleries with museum-quality shows. We want the suburban safety of our youth to cradle us and mask urban blight.

But can we continue to mask Skid Row?

Six months after I moved to Los Angeles to contribute to this narrative of gentrification, Get Down Town asked me to pen an exhibition review of the retrospective of the Los Angeles Poverty Department (LAPD) that took place at the Armory Center of Arts in Pasadena, California. LAPD is a long-running performance art group of homeless or formerly homeless individuals, based in Los Angeles’s Skid Row. Skid Row, which occupies a 54-block radius largely contained since the 1890s, constitutes a significant and historical portion of the political strife plaguing discussions of real estate development in Downtown Los Angeles - the area that this former New Yorker identifies as the portion of the city’s skyline with the densest cluster of skyscrapers. A thriving metropolitan centre in the early twentieth century, Downtown experienced a significant economic decline in the wake of post-war suburbanisation. The neighbourhood “re-emerged” in the late 1990s with a fancy new core—refurbished Art Deco buildings and freshly erected high-rises, seductive neon lights, scrubbed street corners, contemporary art museums, and glittering food halls. Naturally, it’s a fraught trajectory (hello, increased urbanisation) that is being contested deeply by the city’s surviving communities.

Established in 2015 by Phoebe Ünter, Ari Simon, and Ian Gabriel, Get Down Town is first and foremost a neighbourhood guide and arts and culture publication covering Downtown Los Angeles. The third issue of Get Down Town was entirely devoted to art-making in Skid Row. The editorial team wanted to represent the area through the “actual community that lives there and the people that create within its framework” instead of reaffirming the customary portrayal of the neighbourhood as a dirty, violent dumping ground for the city’s homeless. They also wanted to acknowledge that they, as newcomers to Los Angeles and as cultural arbiters negotiating relationships with local institutions and neighbours, were addressing an area and group of artists that weren’t traditionally considered within the bounds of circumscribed arts districts and gallery rows. Aside from reaching out to relevant organisations such as the LA Community Action Network, Skid Row Positive Movement, Fashion District Business Improvement District, Skid Row Housing Trust, OG’S N SERVICE ASSOCIATION, Operation Facelift Skid Row, and individuals such as Wendy Chavez, General Jeff, Deon Joseph, Skid Robot, and Jan Perry—the three met and befriended Ronald Troy Collins, a musician and resident of Skid Row, who informed a significant part of the issue’s content and invited them to access Skid Row’s mysterious nucleus.

If the city’s landscape is a studio, then how does one use Skid Row and what does it mean to use it? For Get Down Town, questions began to brew when Frank Cities produced a publication about the neighbourhood. At the launch, which was also a benefit for Lamp Community, an organisation that provides housing services, attendees comprised the fashionable and the non-profit élite, who had their photographs taken in front of a step-and-repeat. Using homelessness as a cheap aesthetic, Frank Cities treated the inhabitants as mere props, perpetuating a top-down, know-what’s-good-for-you hierarchy. Organisers have coined the term “artwashing” to describe the particular kind of gentrification that is happening in the Downtown-adjacent neighbourhood of Boyle Heights, where a historically activist Latinx/Chicanx community has decided to push back against galleries that have recently opened spaces there.

Weeks prior to my relocation to Los Angeles, one of the most notorious incidents of police brutality occurred in Skid Row when members of the Los Angeles Police Department shot and killed an unarmed homeless man called Charly Keunang, nicknamed “Africa” or “Cameroon,” who became a source of inspiration for one of Collins’s songs. Because the Skid Row community is subject to “therapeutic policing,” the impoverished and drug-addicted are rarely able to move out of Skid Row, punished and fined for small infractions that build up criminal records and prevent them from gainful employment. They cycle through the same motions, living out their lives on the streets because they are threatened and constrained by a ceaseless compliance with authority.

Which artists get to stay in an increasingly expensive, homogenous Los Angeles? A couple years ago, teen-to-adult heartthrob Zac Efron was found wrangling a homeless man in Skid Row. The tabloids caught wind of this incident and publicists scurried to frame the appropriate redemption story following: forgive him, former child star battling an alcohol and drug addiction. Efron, a Hollywood actor with the means to restart, can continue to produce his laughable art, while we learn nothing of his sparring partner, the so-called “vagrant,” whose story is passed over like that of others before him. So, I see Get Down Town’s Skid Row issue as a form of recovery: a reconciliatory strategy rarely afforded to the residents and artists who make Skid Row their home, crafting a present that honours the extant and imagining a more inclusive future.

Collage of artwork made by residents of Skid Row. Credits embedded in design]. Image courtesy of Get Down Town.