Katherine Jackson, photograph from the Context is Half the Work exhibition at Kunstraum Kreuzberg in Berlin [exhibition dates September 12 – November 8 2015]

Katherine Jackson, photograph from the Context is Half the Work exhibition at Kunstraum Kreuzberg in Berlin [exhibition dates September 12 – November 8 2015]

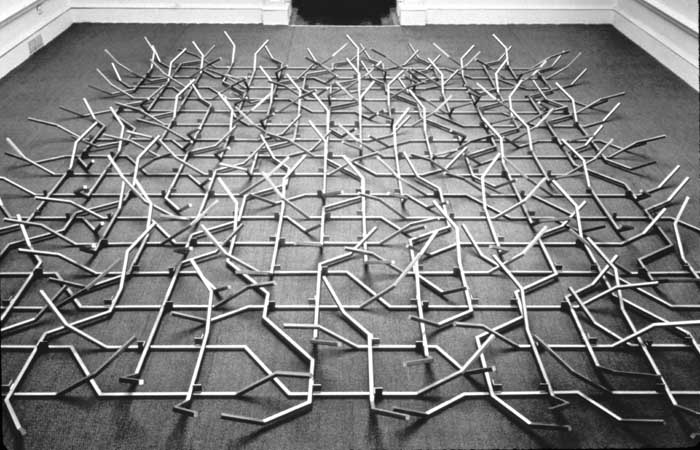

Garth Evans, ‘Breakdown’ Steel, 1971, made in response to British Steel Placement with the APG/British Steel Corporation Fellowship 1969. Image courtesy of Garth Evans.

Art and Industry: The Industrial Negative Symposium and the Artist Placement Group

Katherine Jackson

The term negative implies a counterpart, the underbelly or simply the other. Yet, at the same time, the negative is intricately bound to the successful production of the whole. For example, in photography the negative produces the glossy print. It was this premise that inspired the Artist Placement Group (APG) to conduct the Industrial Negative Symposium in 1968 at the Mermaid Theater in London.1 The symposium’s ambition was to bring together speakers from Art and Industry; two entities that they considered to have had limited contact but yet inextricably linked.

The APG was an action research group of artists founded by Barbara Steveni in London in 1966 in collaboration with artists including John Latham, Jeffrey Shaw, Roger Coward and Garth Evans.2 The APG’s mission was to place artists within Industry; a goal epitomized in their frequently quoted slogan, “The context is half the artwork”.3

The collaborative nature of APG’s attempt to bridge Industry and Art has caused the group to be identified by art historians as an important precursor to contemporary “Social Practice” art discourse.4 However, the APG has also been met with harsh criticism. Critics, past and present, have labeled the group as a failed project, co-opted by the government and industrial initiatives. The following essay argues that the collaborative qualities of APG’s placements have been taken out of context and overemphasised. Further, critics’ accusations of failure have often ignored the group’s definition of art, itself.

The APG formed during an artistic zeitgeist that was highly influenced by the texts of communication’s philosopher Marshal McLuhan and a concern with what was perceived as the acceleration of technology at a troubling pace.5 The desire to leave the studio and engage with the new technological world was combined with an attitude of social responsibility, most notably advocated at London’s Central Saint Martin’s School of Art, where many of APG’s artists were students and later faculty. It was these local and global factors that led to the APG’s participation in an art movement that sought to bring together different facets of society.

According to the APG, Art was to address the industrial and technological realities of society. Art was to become a sort of time capsule. In the words of the APG, “We see in the object now a kind of instant history”.6 Through the philosophical framework of John Latham’s Flat Time Theory, the APG further argued their political ambition.7 Namely, the artist could use the context of industry as a platform to create a new type of economy; an economy not based on commercial interests but on avenues of attention and long-term societal goals…what they described as a “total economy”. The artist was declared by the group as a “proto-type” for the future; an almost mythical communicator that could not only save industry, but society as a whole.8

The Industrial Negative Symposium provided a platform for the APG to argue the benefits of their approach and the potential role of the artist in Industry. But through this process it became apparent that the artists’ themselves were seeking something from Industry as much as Industry was seeking something from Art.

The industrial agenda can be succinctly summarized by a quote from Ray Gunter, the MP from the Foundation of Automation and Employment. He states: “The technological revolution is having deeper consequences than many of us have yet thought. It is not yet understood. Social implications in what these implications will be, in man’s attitude to work, in man’s attitude to the society in which we live. It is not only the redundancy, the unemployment that men fear. It is to the deep underneath the surface disquiet in industry itself”.9 From this excerpt, a deep concern for the implications of new technology in the work place can be seen, specifically in the realm of social and communication consequences. The presence of Gunter and others at the symposium identifies the industrialists’ hope that these potential problems could be eased by the increased participation of the arts in Industry.

The Industrial Negative Symposium is an event that encapsulates the entire APG project; a tight rope between industrialists desire to use art for their own gain and the APG’s desire for artistic autonomy. A position so difficult that artists and critics during that time, most famously Gustav Metzger10, and today’s Art Historian Claire Bishop11 have criticized their idealism and naiveté in attempting to develop a third way between Industry and Art. An avenue that many believed would end and arguably did end with industrial and government co-option of artistic practices. However, these critics fall victim to the same idealism that they fault in the APG.

The choice of the term “negative” for the Industrial Negative Symposium is significant. It is loaded with both philosophical and art-historical baggage. However, what seems most productive in discussing the APG’s use of the term is the seminal Rosalind Krauss essay entitled “Double Negative” (1977). In this work, Krauss describes 1960s Minimalism as a movement away from the “private self” to an exploration of “what the world is like.” In her discussion of artist Michael Heizer’s land-art work “Double Negative,” she states, “The individual is only able to truly understand themselves through a Double Negative”. Krauss further clarifies, “…it is only by looking at the other that we can form a picture of the space in which we stand”.12

The inspiration for the Industrial Negative Symposium by the APG was not so different from what Krauss concluded. The APG was convinced that to better understand the art world, the artist had to occupy the position of the other, the negative…in this case industry. This sentiment is echoed in an excerpt from Garth Evan’s notes during his placement with British Steel in 1968. “My anxiety to decide if the artist might conceivably be a potential contributor to the industrial enterprise was not conditioned by a conception of industry. It was conditioned by a concern with the current situation of the artist”.13

In examining the Industrial Negative Symposium what becomes apparent is that current discourse is asking the wrong questions of the APG. Questions should be centered not on what the APG and Industry felt that Art could do for Industry, but instead what could Industry do for Art? Krauss suggests that the artists of the 1960s sought to look outside the art world to better understand themselves. In the case of APG, they not only placed themselves outside the art world, but they did so in order to develop a new medium for art, the medium of Industry.

Katherine Jackson is a PhD candidate with the University of British Columbia. Her dissertation research examines the shifts in European art production from 1968 to 1979. From post-war optimism to post-Fordist anxiety, she is interested in how artists responded to this era of simultaneous optimism, collaboration and severe anxiety over changing working conditions, labour policy and the influence of American consumerism. Katherine is currently the archives assistant at Flat Time House, the home and archive of Conceptual artist John Latham.

1 ‘Barbara Steveni and The Artist Placement Group’, www.flattimeho.org.uk/apg/

2 For complete list of APG placements see Tate Museum, ‘Artist Placement Group Chronology’, Tate Artist Placement Group Records

3 Artist Placement Group, Tate Archive, London

4 For a definition of “Social Practice” see Bishop 2012; Bourriaud 1996; Creative Time 1990s-; Jackson 2011; Kester 2011; McLagan and McKee 2012; Vishmidt 2013

5 Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: the Extensions of Man, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1964

6 Artist Placement Group, Tate Archive, London

7 John Latham, Flat Time House Archive, London

8 Artist Placement Group, Tate Archive, London

9 Artist Placement Group, Tate Archive, London

10 Gustav Metzger, ‘A Critical Look at Artist Placement Group’ in Studio International, January 1972, pp 4–5

11 Claire Bishop, ‘Incidental People: APG and Community Arts’ from Artificial Hells, Verso, London, 2012

12 Rosalind Krauss, ‘Double Negative’ from Passages in Modern Sculpture, Viking Press, New York, 1977, pp 243–289

13 Artist Placement Group. Tate Archive, London