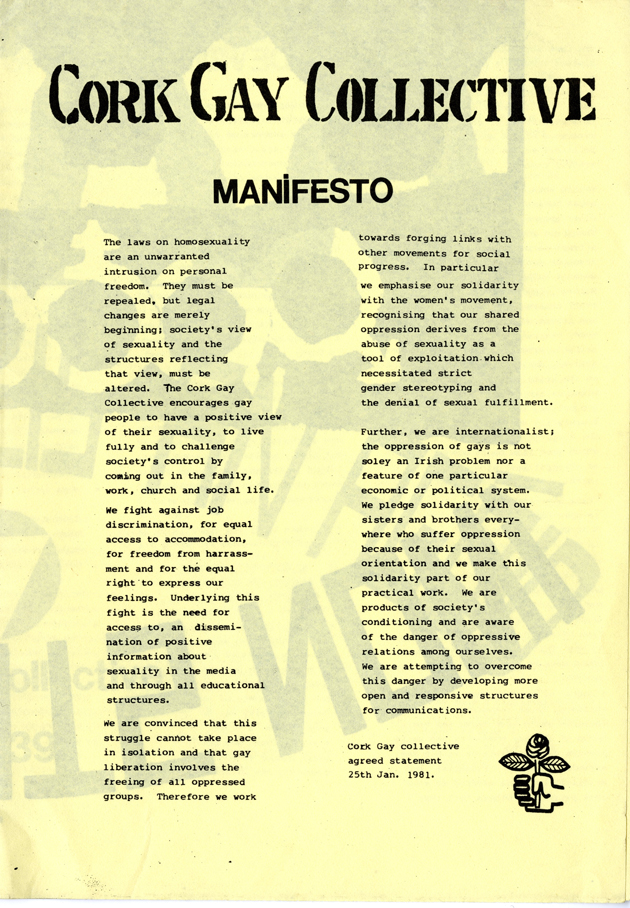

Manifesto Cork Gay Collective, 1980s, © Cork LGBT archive

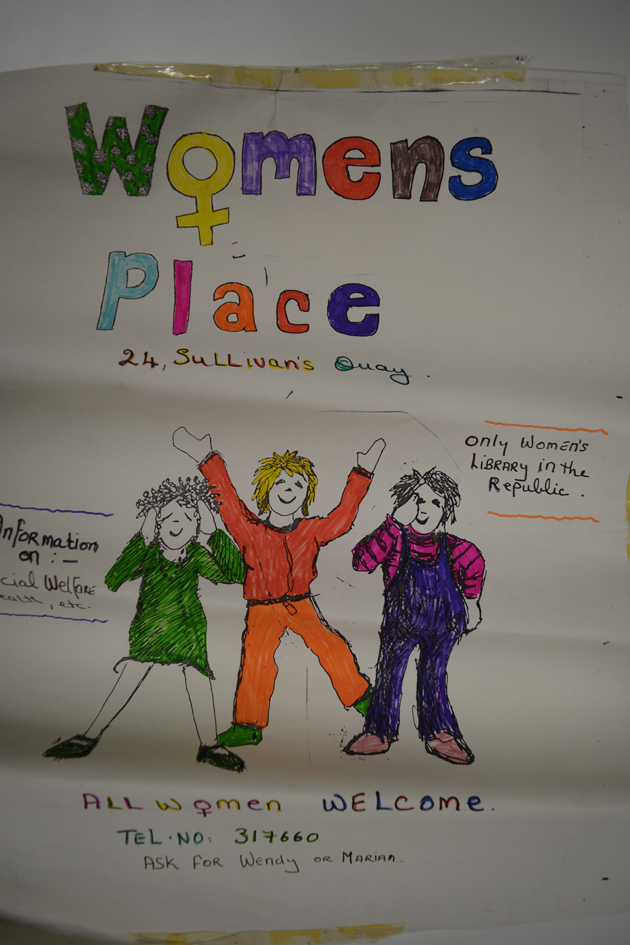

Women's Place, 1980s poster, © Cork LGBT archive

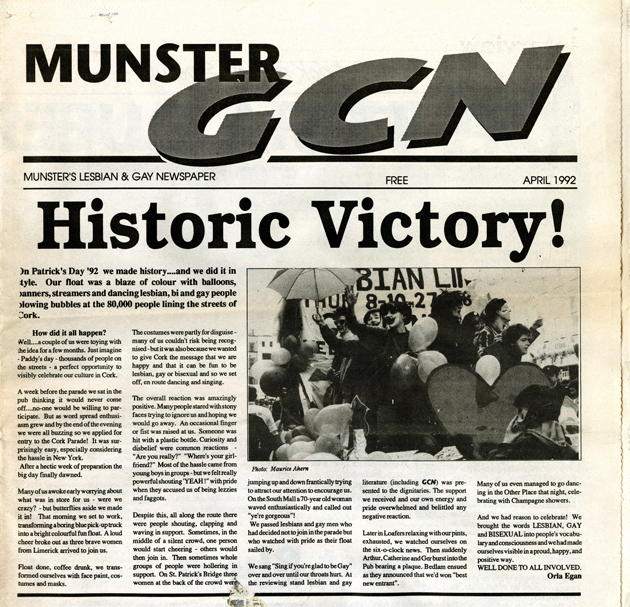

Orla Egan’s article in the Munster GCN, 1992, © Cork LGBT archive

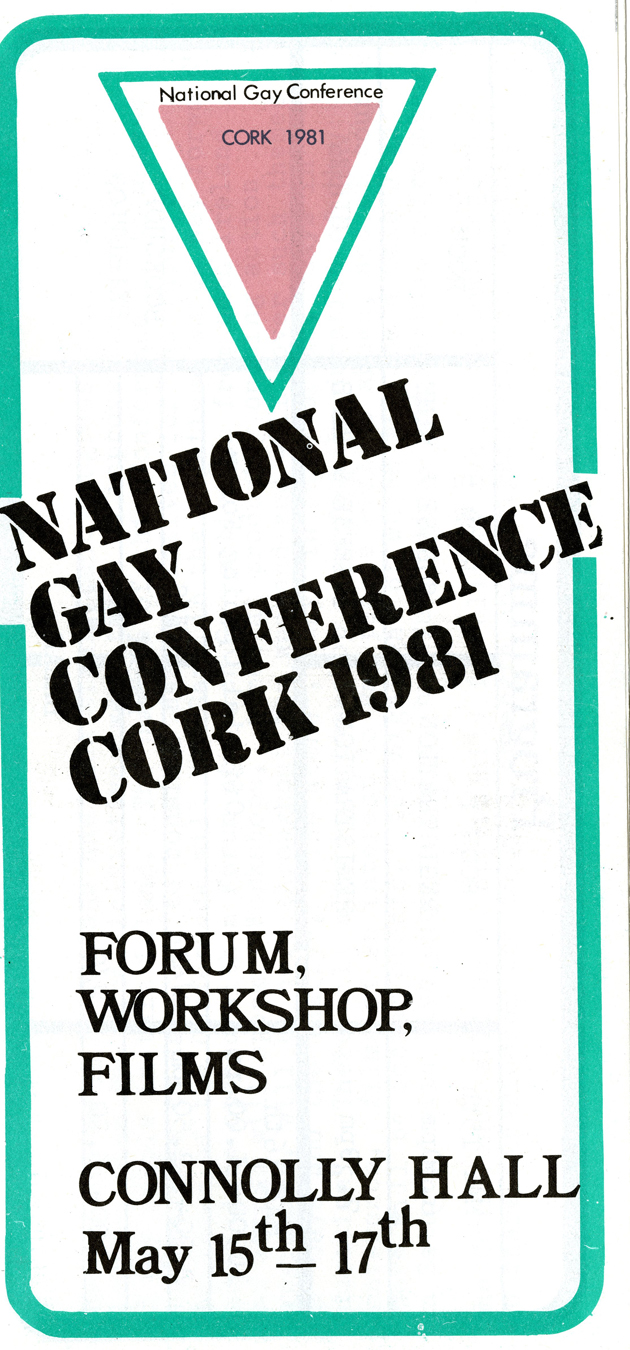

National Gay Conference Cork, leaflet, 1981, © Cork LGBT archive

The Cork LGBT Digital Archive

Orla Egan

This article intends to explore some of the challenges and potential impacts of developing a LGBT Digital Archive. Digital History can open up a multitude of possibilities for the histories of marginalised and excluded communities. Access to archival materials is essential in unveiling previously hidden histories. The development of digital history has created a plethora of new possibilities for the preservation, storage, display and engagement with history and archival materials. It has the potential for the democratisation of access to history as well as the democratisation of the production of history as interactive tools can enable a variety of voices and narratives to be heard. Such work is not without challenges, including access to materials, clarification of copyright issues and the digitisation process itself. It can however help to transform how we do history and create a space for previously unheard or hidden histories to be seen.

Digital History opens up possibilities for the preservation of archival materials that may otherwise be lost. This is particularly important in relation to hidden histories, as access to archival materials is essential for documenting and analysing the histories of marginalised communities. The discipline of ‘History’ has traditionally been presented as objective, as providing unbiased accounts of past events. However, if we examine who and what is included or highlighted, and who and what is excluded, hidden or obscured, we can see that historical accounts are intrinsically political and reflect what and who is valued by historians and by society. Women’s History, LGBT History, Black History, Working Class History etc., have all sought to challenge the exclusionary hegemony within history and to begin to develop more inclusive and nuanced historical accounts.

Knowledge of our past is important for our sense of the present. It is important to be aware of our history, of how we have come to where we are now and to have a sense of pride, belonging and acknowledgement of our community. Using digital tools and methods enables wider access to, and engagement with, historical materials through the Internet and social media. It creates a wider audience and facilitates interaction, contribution and collaboration. In “An Attack on Professionalism and Scholarship? Democratising Archive sand the Production of Knowledge” (Ariadne, Issue 632, 2010), Andrew Flinn calls this the “democratisation of knowledge production.” Flinn talks about the long tradition among groups who have been excluded from mainstream history, and from so-called ‘national’ archives, to gather and share information about their history: “Recently designated as independent or community archives, the grassroots activity of collecting and sometimes creating materials relating to the history of a particular community (self-defined by place, ethnicity, faith, sexuality, occupation, other interest, or combination of these and more) has a long heritage.” Digital technologies, and the development of digital archives, open up opportunities for members of such excluded communities to actively contribute to the preservation and sharing of its history. “Perhaps the most interesting and potentially significant aspect of this is the ability offered by collaborative technologies not only to upload and passively share digital heritage but also to engage and participate in collective discussion and discovery…It also offers the opportunity to share memories and build upon that would otherwise most likely remain uncaptured.”

This is the spirit in which I am developing a Cork LGBT Digital Archive. Cork has a long and rich history of LGBT activism and community formation and development. Since the 1970s, lesbians and gays in Cork have forged communities, established organisations, set up services and reached out to others. Although most of the organisations and activities in the 1970s and 1980s focused on the lesbian and gay communities, with little acknowledgment or visibility for the bisexual and transgender communities. As well as campaigning for LGBT rights and providing services and supports, the LGBT community has played a vital role in movements for social justice and political change in Cork. Yet this community, like many other LGBT communities worldwide, has been largely invisible in historical accounts and its contribution to social and political change and developments largely unacknowledged.

I have been given access to the private Arthur Leahy Collection, which has been gathered since the 1970s, and includes a wide range of materials, including posters, leaflets and newsletters. I have started to digitise these materials. In addition to this collection I am also hoping to access and include other private collections of materials relating to the LGBT community, including oral history interviews.

The main Cork LGBT digital archive is currently being developed on an Omeka site, but I have also been working on a Wordpress site. I am using this Wordpress site to begin to trace a chronology of the main developments in the LGBT community and to encourage interest and engagement in the project. I want to actively encourage and enable the contribution of community members to the knowledge and data contained in the website. I would hope that it would become a website of many voices and many perspectives. This kind of interactive, collaborative work is central to Digital Arts and Humanities. However it is not universally valued or respected within the academic world. In the same article, Flinn points out that one critic of his work suggested that the democratisation of knowledge production was detrimental to the idea of scholarship. “In particular, scorn was reserved for the idea that, in future archive catalogues, many 'voices' might be enabled 'to supplement or even supplant the single, authoritative, professional voice', an idea which was described as being, in extremis, 'a frontal attack on professionalism, standards and scholarship'.”

Unlike the critic mentioned above, I believe that the democratisation of access to, and production of, knowledge, actually sets new and higher standards for scholarship. Digital scholarship make us more accessible and answerable to our communities, who can easily and publicly comment, via our own websites, on the work we are doing. While challenging and enervating, this can only improve the quality of the work we strive to do. I would suggest that there is a huge potential for the fundamental transformation of how we do history, personally, politically and methodologically. It is essential that we critically reflect on who is included and excluded in history, and to strive to find new and innovative ways to research, preserve and share our histories. We need to find ways to ensure that all of us feel reflected in the histories we can access. I would hope that, through creating a LGBT Digital Archive, I could in some way contribute towards this historical metamorphosis.

www.corklgbtarchive.com

www.corklgbthistory.com

www.orlaegan.wordpress.com

Orla Egan is a PhD Candidate in Digital Arts and Humanities at University College Cork.