Hank Willis Thomas, Hospitality is quickly recognized, 1949/2015 (2015). Digital chromogenic print. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

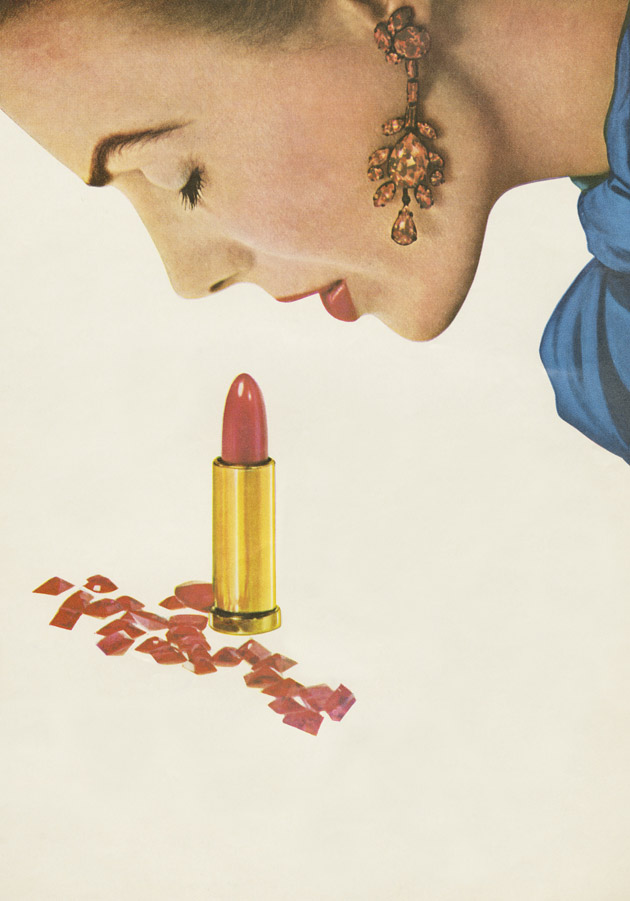

Hank Willis Thomas, Will not go dull and lifeless, 1953/2015 (2015). Digital chromogenic print. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Installation view of the space on 20th Street. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Installation view of the space on 24th Street. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Installation view of the space on 24th Street. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Women and Art Rebranded in the Work of Hank Willis Thomas

Meredith Talusan

One hundred images depicting white women span two enormous galleries in the Chelsea district of New York City, each representing a year from 1915 to 2015. They are taken from advertising images divorced from their original context, and any text that originally accompanied them has been removed. Themes emerge over time: women caring for their families, entering professions and arenas previously reserved for men, handling the latest gadgets of the era. Women displaying their bodies for consumption, representing unattainable beauty, demonstrating a sometimes subtle, other times not-so-subtle, subservience to men. It’s work that’s conceptual, rigorous, political. It’s also a show of artwork by a man depicting women.

In an age of politicised identity, it’s been curious to observe how multiple notices for Hank Willis Thomas’s Unbranded: A Century of White Women make little mention of his gender in relation to his subject. Having observed how women artists of the 80’s and 90’s, led by the Guerrilla Girls, have loudly critiqued the assumption of male artist as maker and women model as subject, it’s striking to observe the lack of commentary over Thomas mounting a show as a male artist, not only with women as his exclusive subjects, but where the images he appropriates largely assume a male gaze.

A major factor in the lack of gender commentary on Thomas’s appropriation is his position as one of the most important black artists of his generation, well known for his enduring exploration of black male identity through corporate imagery. Thus, Thomas in multiple interviews has emphasised this exhibition as an extension of his previous work on the artificiality of race. Critics have largely ceded the artist this conceptual ground, even though art in its very nature leaves itself open to multiple receptions. In this given case, it’s not as though understanding Thomas’s work explicitly through the lens of gender is any stretch, given that the bodies on display in his show are not only coded by their whiteness, but also by their womanhood. To avoid the complexities and paradoxes of Thomas’s expansion into female territory, intricately tied to both the artist’s black male identity and creative history, would be to do a grave disservice to his art and its social meaning.

I use the metaphors of territorial expansion deliberately here, at a time when the sphere of social influence has become a more salient marker of status than actual physical space. This sphere translates into capital now just as the possession of territory exclusively by white men did in previous centuries. Thomas’s exhibition follows Unbranded: Reflections in Black from Corporate America in 2008, which suggests that Unbranded: A Century of White Women is a sequel of sorts to the original. By moving on from unbranding black people to white women, Thomas is in fact expanding his own art brand, exerting his influence over another market segment like a men’s clothing line going into women’s wear, keeping in mind that art today participates in and even arguably exemplifies the commodity culture to which he directs his commentary.

For Thomas, depicting white women is an astute manoeuvre that intersects conceptualism, politics and marketing, and one that allows him not to be pigeonholed as a black artist who only explores explicitly black subjects. Thomas presents himself as not limited by an art world that still disproportionately values white maleness, but rather as one who should be valued for the strength of underlying and expansive conceptual ideas beyond specific identity, largely thought to be the province of white men: Duchamp, Rauschenberg, Haacke, etc. Thomas’s art, apart from depicting a century of white womanhood, also stands at the endpoint of conceptualism’s first century, which marks its origins in Duchamp’s Fountain of 1917, and is widely considered the most important art movement of our time, associated with overarching concepts such as the contemporary and postmodern in ways that identity-driven art is not.

Certainly, Thomas’s most cunning move is his enactment of brand expansion through the eyes of white men. Rather than transforming advertising images, making a mark, creating an interruption, as he has in previous work on black male imagery, Thomas instead removes distraction to reveal the white man’s message about white women. It allows his work to function as critique yet absolves him of the charge of speaking for women, robbing them of agency as he points a finger at other robbers. It’s as though his job is not to create but to tidy things up and make them presentable, methods that are usually associated with helpers rather than masters, even as these seemingly trifling actions make the interests of white-male led corporate culture more overt. Just as enslavement and servitude were conditions of blackness, whose legacy endures to this day, passivity and delectable availability were also conditions of womanhood that continue to hold sway over women’s lives, ones that allow the continuation of a system that unjustly bestows economic rewards on white men.

A concern, of course, is that Thomas enacts his art not only through white men, but also on the bodies of white women. His work produces not only critique but also objects of consumption, a way of questioning the norms of womanhood while repeating the display of the unattainable and objectified female subject. Most of Thomas’s pieces wouldn’t be out of place in male-dominated corporate board rooms, available for admiration by the very people they are meant to critique, divorced from their original context, or perhaps brought back to the mines of white male privilege from which they came. In fact, Thomas’s art makes the display of women’s bodies more rather than less acceptable in these contexts, layering a political patina on top of female objectification. This function of Unbranded thus exists alongside its more liberatory meanings, as the ramifications of all art are multiple.

Yet to damn Thomas for his imperfect ideology only serves to hold him to a higher standard than any artist working under capitalist conditions. Just as advertisements must abide by certain parameters to sustain their makers, art as in any social arena leaves space for challenge while setting its own boundaries. With Unbranded: A Century of White Women, Thomas points to the possibility of a minority art that can exceed its own borders to be thought of as simply art, encompassing the world with an ambition still connected to and assumed of white male artists. Thomas’s is an art that demands to be re-perceived through concept rather than identity, extending its reach using methods both specific to the influences of his black male experience, yet indefinitely expandable. For Thomas, to unbrand women is to brand himself, and to rebrand his art for social realms where those of his race have long been excluded.

www.hankwillisthomas.com

www.jackshainman.com

www.aselfmadewoman.com

Meredith Talusan is a Filipino-American transgender writer, artist, and advocate.