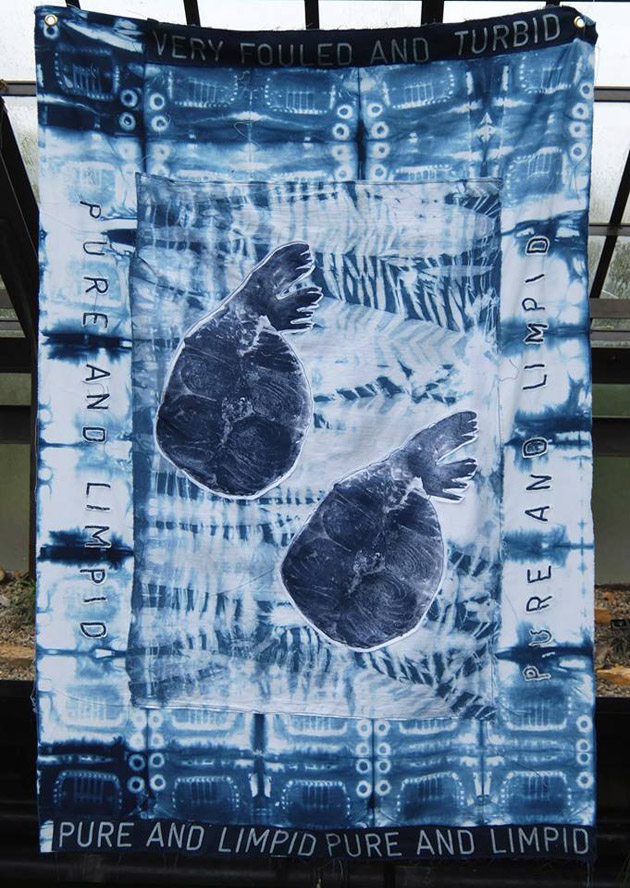

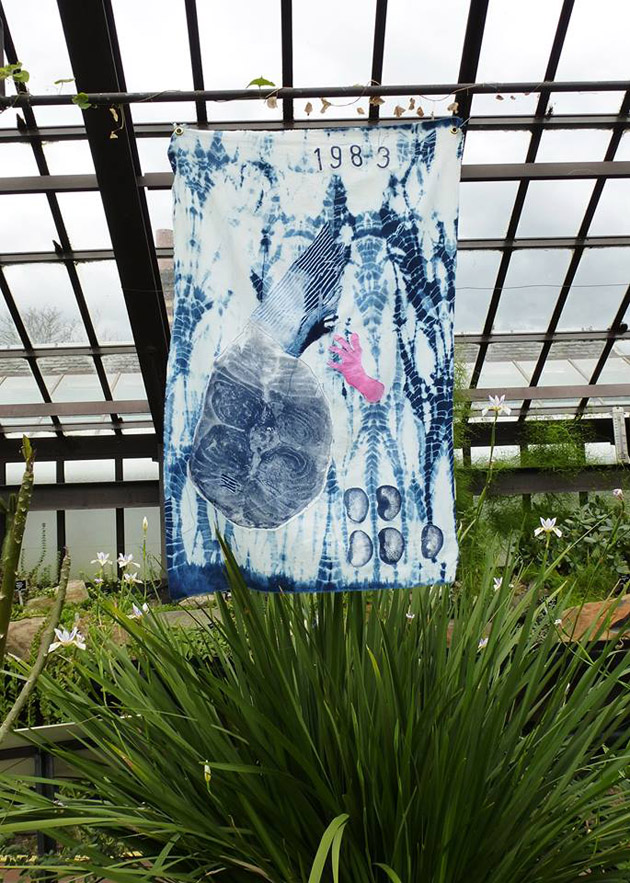

Hand dyed shibori lawn cotton, screenprint on cotton, embroidery thread. © Josie Rae Turnbull, 2015.

Commemorative Salmon Spawning Quilts

Josie Rae Turnbull

I was recently part of a group show in Glasgow’s Botanic Gardens with fellow Glasgow based artists Fionn Duffy, Abigale Neate Wilson and Alex Kuusik. We explored the garden’s hidden industrial past, focusing specifically on the Arboretum’s former guise as print and bleachfields, where fabric would be soaked in stale urine and bask on tenterhooks on the banks of the River Kelvin, before being dyed. These processes were then subsumed by the industrial revolution, particularly Charles Tennant’s invention of chemical dyes and bleaching powders. The symbiotic relationship between human intervention and cultivation of the natural is one that was reflected in the pieces we produced and displayed in the main range of glasshouses and the Arboretum itself.

St Rollox, aka St Roch or St Rocco, is the patron saint of dogs, the plague, plasterers, and laundry workers, and is usually depicted with a dog licking the plague sore on his leg. St Rollox was also name of Charles Tennant’s chemical works in Glasgow, which by 1830 covered nearly 50 acres to become the largest chemical factory in the world. The powerful pollutant meant that acres of land were covered by solid waste. The 132m towering chimney which eructated the gaseous emissions was known as Tennant’s stalk, this local landmark’s name reflected my interest in the absurdist human interventions and warping of the natural.

In the mid 20th century the Kelvin was still strongly polluted by industry, the paper works proffering strong alkalis, and detergents from St Rollox making it frothy. I wanted to directly mimic the techniques used at the time, using synthrapol to strip and prepare the fabric, experimenting with discharge dyeing with bleach, and hand dyeing with both natural and machine indigo dyes.

My individual research honed in on salmon and their spawning site in an area of the River Kelvin. Salmon returned to the site in 1983 after an absence of 120 years, the period in which nothing but a particularly resilient sludge worm - Tubifex - was able to survive in the fouled and turbid river. Although The Scottish Herald celebrated the salmon’s homecoming with a triumphant photo and headline announcing the “RETURN OF THE KINGS”, it was an ambivalent and acrid occasion. As one woman put it pertinently, “Aye you’ve got Maggie Thatcher to thank for your salmon, she’s shut down awe the industry in Lanarkshire”

I started to think about John Berger’s book Why Look at Animals (2009) and the reduction of animals into spectacle, swimming along a foot wide pipe to the processing plant. They are synonymous with Glasgow, their presence on the city’s crest owing to a monk plucking the Queen’s lost ring from one’s stomach. They also relate to the interesting relationships between botanic gardens and colonialism; wild salmon dying of sea lice and other diseases caught from farmed salmon; the fact that we import fish from South America to feed the fish in Scotland; and wild fish from the Northern hemisphere being intrinsically polluted from high levels of industrialisation. Some allege that Scotland’s over-farming of the fish is to meet demand for sashimi in China, in exchange for the two pandas in Edinburgh’s zoo.

Spawning salmon require suitable grades of gravel bed, and I hope they find these quilts suitable bedding. The pattern of one of the quilts was created using a bicycle pedal as a resist in the folded fabric, as transportation is the traditional gift one gives your spouse on your 32nd wedding anniversary. My work always involves entropy, and the Shibori processes I utilised mimic botanical striations and the idea of natural chaos and order. I ensured that the objects I was using as resists and binding materials reflected the context of the work, including clothes pegs, bicycle pedals, metal washers, natural twine, washing line, which all left ghostly imprints and negative impressions.

Indigo dye is the worst thing I have ever smelt, like a bizarre sharp boiled chicken, but brewing it does makes you feel connected to the retching legacy of chemical workers, mixing up litres of it in an overpriced tupperware vat, the elastic on my marigold glove snapping and giving me an indigo hand for a week.