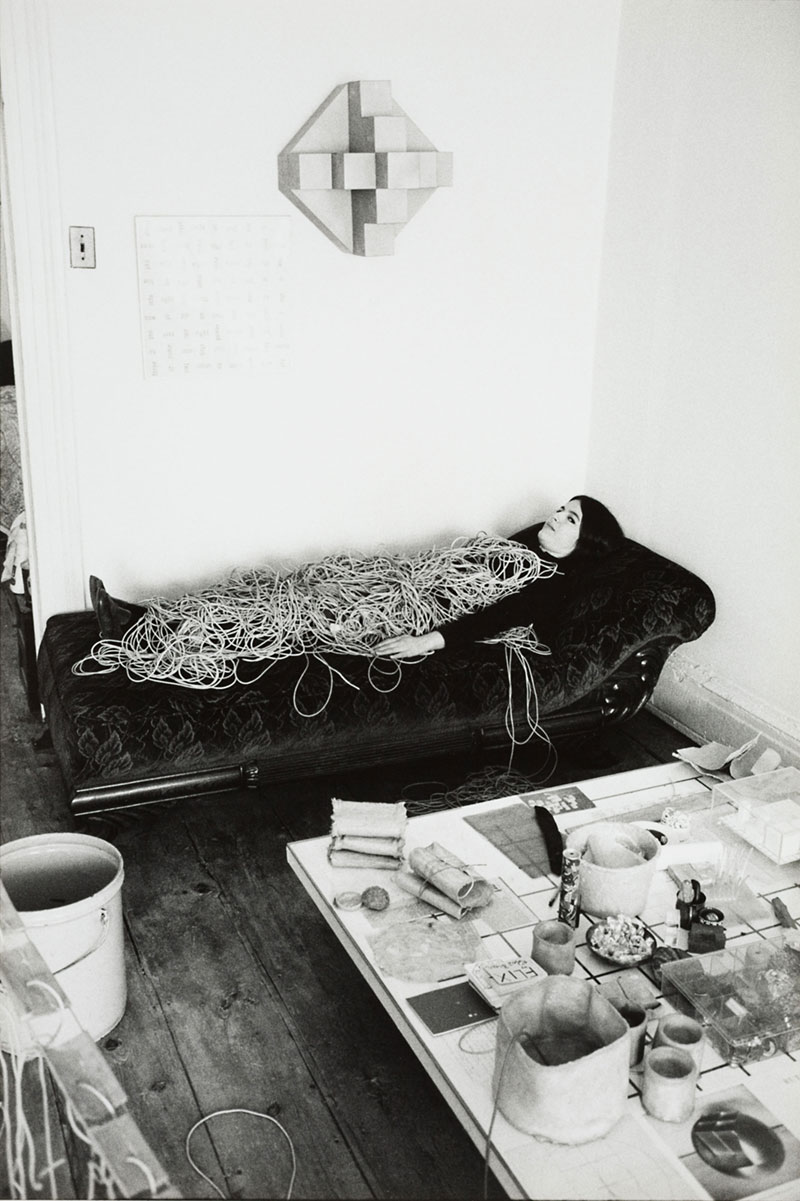

Eva Hesse in 1968, photo from Herman Landshoff, in Eva Hesse, a film by Marcie Begleiter, a Zeitgeist Films release, 2016

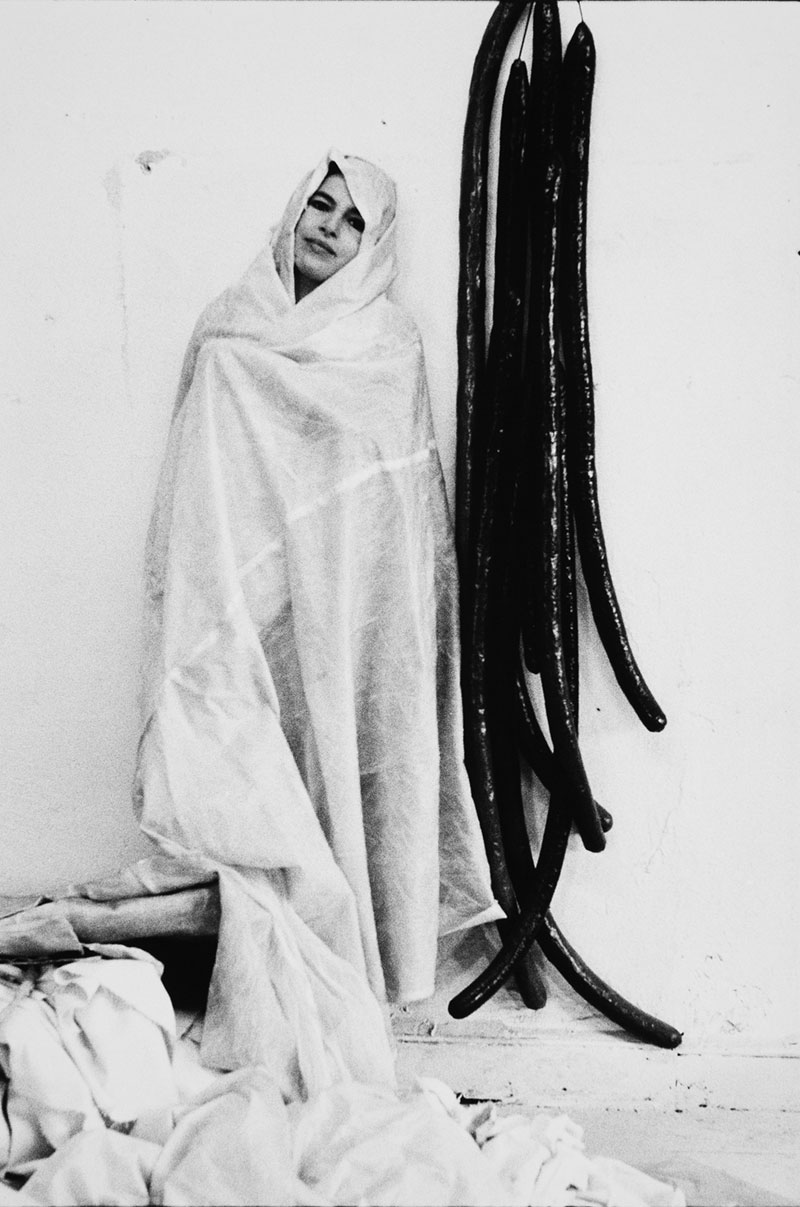

Eva Hesse in 1966, photo from Gretchen Lambert, in Eva Hesse, a film by Marcie Begleiter, a Zeitgeist Films release, 2016

On Eva Hesse

Lily Evans-Hill

It is so bad its good. This neutralises opposites. Reconciling the two major attitudes towards art which are mutually opposed. ART as art. ART as life. Eva Hesse wrote this in a notebook of 1968, when her career as a sculptor had been established with her first solo show, Chain Polymers, at the Fischbach Gallery in New York. She had also been exhibited at the Anti-Form show at the John Gibson Gallery and again at Lucy Lippard’s travelling show Soft and Apparently Soft Sculpture with Louise Bourgeois, Bruce Nauman, and Yayoi Kusama. Increasingly well known in the art world and starting to achieve recognition in the public sphere, Hesse’s work began to span across art publications nationwide and in the writing of her peers. However, her own words did not appear until her contribution to the Art in Process IV show at Finch College in 1969, and more noticeably, with the publication of an interview with Cindy Nemser in the May 1970 issue of Artforum, rushed to print a few weeks before her death. It would later serve as her only public statement about her life and work. Hesse’s work had become increasingly recognised, yet no statement of her own practice had been published, unlike many of her contemporaries who—as Lippard prophesied in her article stating the dematerialisation of the art object in 1968—became theorists themselves. Hesse’s conceptual process, unlike that of Morris, Judd, or Flavin who wrote extensive studies on their work and that of their peers, was largely unknown until her death.

Hesse’s words do exist, however, in her journals and writings left to her sister. These were subsequently used in Lucy Lippard’s monographic book about Hesse, published in 1977, and held at Oberlin College thereafter. The transcribed and edited version of her writings and diaries became widely available in their published form, 40 years later, with the publication of Eva Hesse: Diaries from Yale University Press in 2016. In the same year, Donald Judd’s complete and extensive writings were launched into reprint. These offer a contrasting example of ‘writing in the age of Minimalism,’ to Hesse’s rough working notes and personal anecdotes about her dreams, her troubled relationship with her husband, her fathers death, and her curious letters of encouragement addressed to herself. Perhaps this is the perfect contrast to understand the stakes of Hesse’s writings, and how we might employ them to understand not just the artist, but her negotiations of artistic practice, and the lessons she might be able to teach us about making art as a woman, and as an immigrant, in the all-American male world of minimalism.

The journals are substantial and span her whole career. They show a keen interest in the theoretical underpinnings of art, as well as her detailing of experiments and workings for her objects. A striking number of pages are dedicated to Hesse’s reading of art theory, philosophy (many entries are dedicated to the writings of her peers such as Morris and Lippard), and notes from lectures she had attended. Hesse’s engagement with contemporary criticism shows that, just like her published artist siblings, Hesse was keen to theorise, contextualise, and conceptually augment her own work. Within these pages, she presents a close and critical understanding of Minimalist practice, and thinks Minimalism and subjectivity in the very apt private setting of her journal. Minimalism and serial art championed the non-subjective, and understood art as having the potential to produce a phenomenological viewing process, where its intentions were to make the viewer aware of space and interaction with the object. The mechanical rigidity of Donald Judd’s boxes, Dan Flavin’s lights, and Sol LeWitt’s grids—three-dimensional shapes repeated in close succession—their objective presence drowns out the subjectivity of the artist, as they become objects for objects sake. Hesse writes that these works are ‘shadows in structure, [they] disregard history, [they] devalue emotion’. Minimal and serial practice is a refusal of the expressive gesture, a refusal to perform subjectivity in both the emotional and biographical sense.

The serial attitude, Mel Bochner writes, displaces subjectivity in order to champion serial methodology, something Hesse works with in her use of repetition, unremitting minimal gestures, and an incessant process that mouths minimalism, but is complicated by ‘personal tactile confrontations’. Instead, using the mainstays of Minimalism—seriality and repetition—Hesse created works that conformed to an anti-subjective logic in as much as they repealed the rules of serial art practice. Returning to her diary, she writes, ‘serial art, is another way of repeating absurdity’. This process produces the central paradox in Hesse’s art, and it is only when combining seriality and subjectivity that differences appear, and in merging the two did Hesse reveal the emotional and sensual life of the minimal object.

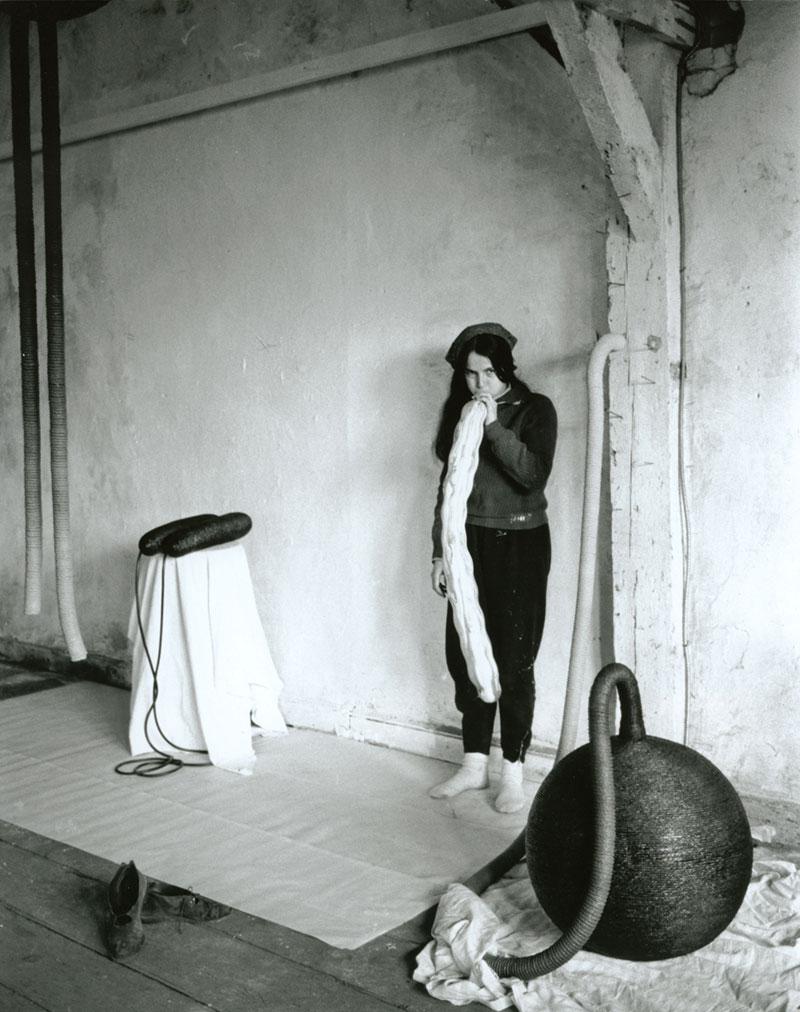

In a press release for the Anti-Form show, this passage employs the same dialectical attributes to introduce her work. I quote: ‘the core of Eva Hesse’s art lies in a forthright confrontation of incongruous physical and formal attributes: hardness/softness, roughness/smoothness, precision/chance, geometry/free form, toughness/vulnerability, natural surface/industrial construction’. While her single shapes, neutral colours, and strict repetitions are related to those of her primary or minimal colleagues, her geometry is always subject to curious alterations, and her repetition takes on an obsessive tinge. A large fiberglass box reveals an interior of translucent tendrils, in rubber floor pieces, lines of lumpy semi-spheres and spheres are ordered by a grid system, a modular wall piece folds and flops disarmingly when it reaches the ground, battered bucket shapes band together in a unified grouping. Hesse consciously played with these opposites, stating that they are ‘witnesses to ultimate union’. She also wrote her own opposing statements about her visions for her work, ‘flexible but still, kinaesthetic but passive, potentially dynamic but frozen’. Employing dialectics, Hesse was able to derive from Minimalism a narrative that allowed subjectivity to speak. I believe that this wasn’t just an endeavour for personal gain. Accepting seriality and acknowledging difference, is an important lesson in the history of art, but more importantly for women’s creative practice, that we might learn from Hesse today.

Lily Evans-Hill is a researcher in feminist art and writing. This text was delivered as a reading before the Orlando screening of Eva Hesse (Marcie Begleiter, Zeitgeist Films, 2016) at the Horse Hospital in February 2018.