Atamari. Kondolenz für Pina Bausch am Opernhaus in Wuppertal, 2009

Clau Damaso, Cravos by Pina Bausch, Lisbon, 2005

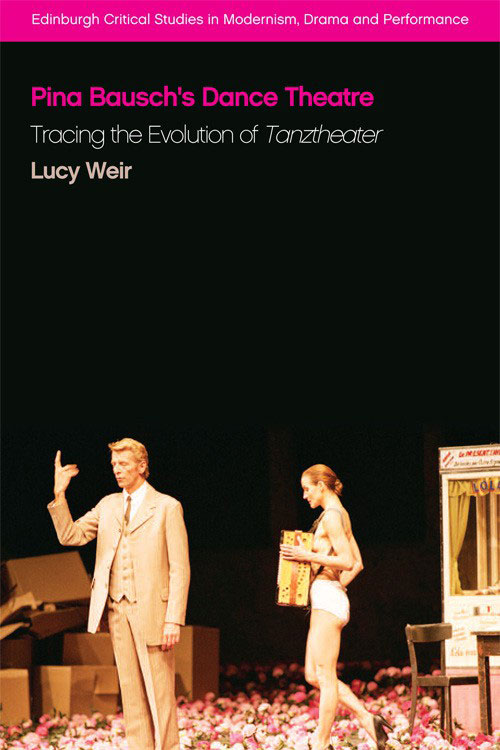

Lucy Weir, Pina Bausch’s Dance Theatre: Tracing the Evolution of Tanztheater, published by Edinburgh University Press, 2018

Bodies of Work: Pina Bausch’s Legacy

Lucy Weir

Pina Bausch, dancer, choreographer, and pioneer of a radical creative method, died on 30 June 2009, only a few days after being diagnosed with cancer. Her company, Tanztheater Wuppertal, was on tour in Warsaw at the time, and the dancers were informed of her passing a few hours before they were due to go on stage. A collective decision was reached to go ahead with the performance. By the intermission, the tragic news had filtered through to an initially unknowing audience. At the close of the piece, the cast came on stage for a single curtain call, leaving a space in the middle of the row where Bausch ought to have stood.

Bausch was a revolutionary, one who evolved an entirely new language of dance. Despite facing significant criticism in her early years at the helm of Tanztheater Wuppertal, she is now recognised as one of the most radical choreographic innovators of the twentieth century. By the time of her death, her work had accrued major international awards and reached worldwide acclaim: a cameo appearance in Pedro Almodóvar’s Hable con ella (Talk to Her, 2002), and Wim Wenders’ posthumous tribute Pina (2011), brought her Tanztheater (dance theatre) to global audiences outside of the dance world.

Over the course of a career that spanned four decades, Bausch produced an extensive body of lengthy, surreal, life-affirming works. Yet only rarely would she physically materialise on stage, appearing in a handful of pieces across her entire repertoire. Rather than locating herself at the centre of her choreography, she devised a new movement vocabulary, creating pieces out of fragmentary gestures, memories, and life experiences. Bausch delved into her dancers’ childhood memories and personal histories in order to form her productions, ‘collecting’ movements and arranging them into the non-linear structure of each work. Dancers would be posed sets of questions or ‘prompts’, to which they would respond individually while Bausch observed the entire process. Each piece is usually titled with a colon, after which they are denoted as ein Stück von Pina Bausch (a piece by Pina Bausch).

Despite this identification of a single ‘author,’ Bausch’s pieces are in fact a composite of experiences, innovations, and memories, many of which are drawn from the company members. The creation of these large-scale pieces necessitates a significant level of trust between choreographer and cast, requiring a demanding degree of engagement and sacrifice from the dancers. Bausch thus became a collagist, piecing together the efforts of the collective group and synthesising the movement into a more homogenous vocabulary, making works with, and upon, the bodies of her dancers.

In the years since Bausch’s sudden death, considerable changes have taken place in the organisation of her company, including the repertoire that it performs, and the ways in which new work is created. This period of flux has run throughout the course of my own research process; I began my doctoral studies in 2009, only three months after her death, and published my monograph on Bausch’s oeuvre in May 2018, by which point the company had begun staging new productions by external choreographers. For the researcher, grappling with Bausch’s legacy in the decade following her death has raised a number of challenging questions: how should her body of work be historicised after her death? As this is an oeuvre made through a collective, collaborative process, what happens to the repertoire as dancers leave the company, or as their bodies age and their capacity is reduced? Perhaps more pressingly, how are pieces are made in such an intimate, personal manner passed on to new cast members?

In most dance companies, whether classical or contemporary, generations of dancers pass on choreography through tried-and-tested means. Traditionally, the duty lies with the roster of ballet masters, retired professionals who hold an intimate knowledge of the material and teach the steps to a new dancer through individual instruction. Dance notation can provide a more accurate representation of choreography than relying on an individual’s recollection of the steps (what dancers often refer to as ‘muscle memory’). Notation strips away some of the subjectivity associated with this kind of pedagogy, as the movement can be recorded in a similar manner to a musical score.

With Bausch’s Tanztheater, however, her unique language renders the use of dance notation all but impossible. Similarly, while a theatrical script might aid in memorising lines of dialogue, the resulting productions cannot be accurately condensed into text alone. Written transcriptions do not fully convey the thematic atmosphere of the piece, and capturing movement on film cannot fully embody the nuances of her dancers’ individual performances. For Tanztheater Wuppertal, reprising older works and passing on individual roles can only be achieved through a combined effort, uniting the expertise of current and former dancers with less ephemeral choreographic traces, such as filmed footage and rehearsal notes.

Dance companies are not static, and their composition tends to change frequently as a consequence of the physical exertions of the job. The career of a professional dancer is not lengthy: the body can only endure an intense schedule of training, rehearsing and performing for so long before a dancer must step away from the stage. In the ordinary course of a company’s touring schedule, roles are regularly handed down or substituted due to illness or injury, for instance. The variability inherent in the dance environment presents a particular challenge to Bausch’s working method: how does one begin to restage a work created not only upon, but also in collaboration with, a specific cast? Similarly, how can a role be accurately portrayed by another dancer when its origins lie in personal memory or experience? In considering these enquiries around authorship and inheritance, it becomes clear that Bausch’s dancers become not only co-authors of the work, but also rehearsal directors, and the custodians of a distinctive legacy. The collaborative method adds a further layer of complexity to the process of archiving and reviving Bausch’s works. Her works are not framed around linear narrative patterns.

It is with this complexity in mind that I return to the question of authorship: how do we reconcile the label that denotes each work as ein Stück von Pina Bausch with this complex and collaborative approach to choreographic practice? My research has led me to conclude that Bausch’s artistic signature becomes a synecdoche, a part for the whole, melding together the bodies of the company with the body of work.

In the period following Bausch’s death, Tanztheater Wuppertal has revived a number of earlier productions from its repertoire. Pieces brought out of obscurity will inevitably change over time: with each performance, subtle changes occur, but as the gaps between stagings grow longer, the connection to a production’s original script becomes less distinct. Equally, with each new cast member taken on, the effect alters further. As more dancers are recruited, a new generation of the company has emerged. The youngest members of Tanztheater Wuppertal never met Pina Bausch, and thus have not experienced her creative method first-hand. Now, they perform alongside those who worked intimately with her—for many, across a span of several decades. Yet it is this contrast that, I suggest, has helped to keep Bausch’s body of work alive. Tanztheater Wuppertal is unlikely to fossilise, to become a historical repertoire company, while generations of new dancers are brought in to breathe new life into her work.

My own experience bears this out: in 2017, I travelled to Wuppertal to see the restaging of Bausch’s Arien (Arias, 1979), a piece that felt all the more joyous, vibrant, and contemporary performed by a collective body of new, young dancers and more seasoned company members. The repertoire – the body of work – is similarly growing, with new choreographers coming on board to create work in the spirit of Bausch, but under different authorship. As these evolving bodies (of dancers and of productions) continue to grow, Tanztheater’s audience continues to expand on a global scale. While Bausch may no longer be with us, the body of work she bequeathed to the world is ever-evolving, and very much alive.

Dr Lucy Weir is a specialist in modern dance and performance, based at Edinburgh College of Art, the University of Edinburgh. Her research interests span the fields of live art, theatre and dance, and queer culture and gender studies. She received her PhD from the University of Glasgow in 2013 and has held several teaching and research fellowships. She previously taught at the University of Glasgow and Glasgow School of Art, and is a Visiting Lecturer at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. Her book, Pina Bausch’s Dance Theatre: Tracing the Evolution of Tanztheater, presents a new reading of Bausch’s work, orienting it within an international legacy of performance practice. This text was commissioned in relation to the Orlando screening of One Day Pina Asked (Chantal Akerman, Icarus Films, 1983) at the Horse Hospital in April 2018.