All images of One Day Pina Asked (1983) courtesy of Icarus Films

On Chantal Akerman’s Pina Bausch

Alice Blackhurst

In 1992, Giorgio Agamben seminally claimed that, |the element of cinema is gesture and not image”/ Chantal Akerman’s 1983 film, One Day Pina Asked, translates such a thesis to the screen: encouraging its audience to perceive, sense, and intuit its expansive sequences, rather than to see them through a blinkered lens. As opposed to asking, ‘How should a film about dancers look?’ it dares to consider how a film about dancing might feel.

The feature tracks the German choreographer Pina Bausch’s Wuppertal, Germany–based dance troupe as they toured their singular hybrid of dance and theater, Tanztheater, for five weeks around Europe. Though later documentaries, such as Wim Wenders’ 2011, first-name-basis feature Pina would attempt to construct a holistic, canonical portrait of the artist, Akerman’s film, resisting any direct-to-camera testimonies, establishing shots, or chronological orientation in space and time, is a tribute that preserves the fragmentary and the piecemeal. It proceeds, according to Akerman’s voiceover early in the film, by “traces and sensations,” often showing slivers of a seminal Bausch dance through partially closed doors, or blurred windows. Commenting on the fundamental ephemerality of dance as artistic medium, the dance-artist Yvonne Rainer, who was a peer of both Akerman and Bausch, and worked with Akerman’s primary cinematographer, Babette Mangolte, once starkly evaluated that “Dance is hard to see”.

In One Day Pina Asked, the resistance of Bausch’s choreography to lucid transparency is presented as ontological condition, rather than as problem to be solved. In obscuring the whole picture, Akerman both gets to gently remind the spectator of the unassimilability of art’s residues to representation, and to return to a career-long interest in what eludes cinematic exegesis, or what it means to, as the child of two Polish-Jewish Holocaust survivors, constantly skate around the edges of a genealogy—in the director’s words—“full of holes.” Both artists—Akerman born in exile in Brussels in 1950, and Bausch born in 1940, near Dusseldorf, in the midst of the brutal war—grappled with the fall-out of inheriting an impossible historical legacy: a legacy that strains underneath attempts to do it justice and produces manic flights of exuberance and violence that resist decency, straightforward interpretation, or common sense.

Akerman has often been asserted as a ‘hyperrealist’ artist of the everyday; an auteur who, in her filmmaking, seeks to index the postures, scenes, and textures of quotidian life often excised from traditional, or commercial, narrative attention. Her most famous ‘breakthrough’ film, Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), a three and a half hour epic of the interior—filmed when the director was just 25 years old—lavished narrative time on the domestic choreographies and existential ennui of a fictional widow in her fifties who, while her son is away at university in the afternoons, trades as a prostitute in her upstairs bedroom to keep her precarious household afloat. Nodding towards the canny subversion of spectator gratification being radically wielded by Akerman here, the audience—in an incisive twist of expectations—is made to confront the lurid boredom of Jeanne Dielman peeling potatoes, preparing veal cutlets, or washing dishes in durational ‘real time,’ while the prostitution scenes are kept elliptically, enigmatically, at bay.

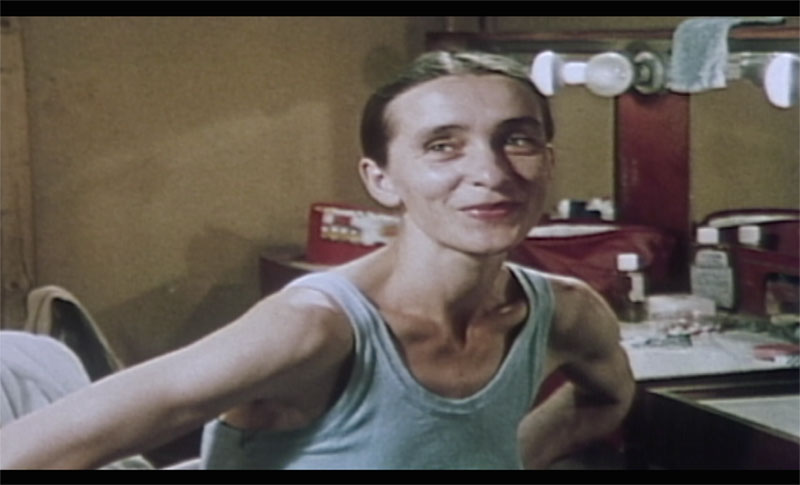

Akerman extends this interest in the minor, interstitial gestures that often fail to surface from the cutting room floor—or in her words, the “images between the images”—in One Day Pina Asked, which often screens the glamorous, internationally feted, and diverse cast of Bausch’s troupe engaging in banal acts such as smoking, putting on makeup, or simply idling backstage. Pushing back against biography’s tendency to file away the numerous rough sketches of rehearsals which precede the pristine halo of the finished work or final performance, these scenes are composed with as much meticulous care and importance as the moments where we see Bausch’s singular artistic vision being animated on an elevated stage.

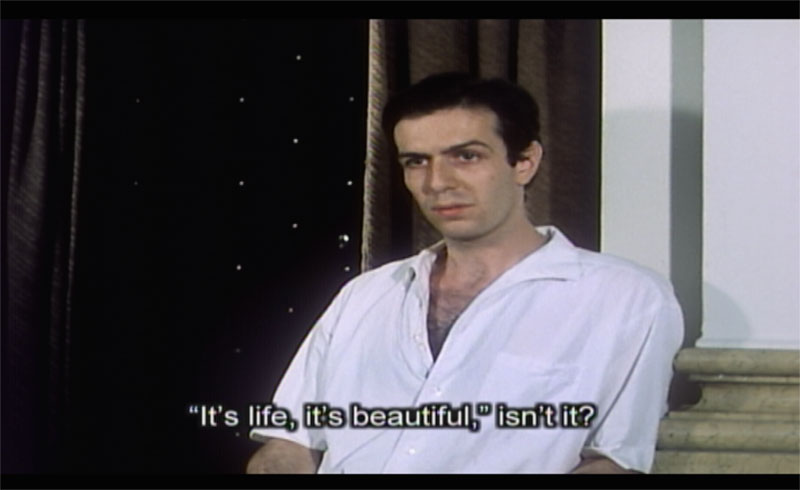

In one stand out moment, Akerman records a young male member of the company rehearsing a sign-language translation of George Gershwin’s popular song ‘The Man I Love,’ singing flatly along at the same time. Stripped of the grandiosity of the lights, the staging, and the attendant musical score that we see fleshing out the number later, the sequence is imbued with tender intimacy and raw affect. Rather than hitting the notes, or executing the gestures flawlessly, it is the gap between effort and perfection, or the straining towards mastery, which touches the spectator. It hits—precisely in its lack of precision—a defiant nerve. In Ivone Margulies’s reading, without the soundtrack of accompanying tangos and other scores, Akerman’s emaciation of Bausch’s productions to their bare essentials drains the pieces of their transcendental lure. Yet in integrating Bausch’s aching, anguished movements into everyday choreography, and reimagining them as a repertoire of postures that might helpfully orientate bodies in space, Akerman points to her interest less in transcendence than in immanence: a sensuous inhabitation of the present moment that might help to establish modes of continuity as balm against the horrors of the past.

While best-known for her largely silent and Hopper-esque domestic tableaux, vibrant strains of music and dance recur frequently within Akerman’s filmography, which acknowledges genres as diverse as the anthropological documentary (South, From the Other Side, Over There, From the East, made during 1993-2006); the literary adaptation (2001’s La Captive or 2011’s La Folie Almayer) and, perhaps most unexpectedly, the musical comedy, loosely inspired by the work of Jacques Demy and Agnès Varda and brought to fruition in two films by Akerman: The 1980s, from 1983, and Golden Eighties, from 1986. In one of Akerman’s most autobiographical films, Portrait of a Young Girl at the End of the 1960s in Brussels (1994), tangentially sculpted after the director’s own-coming-of-age as a queer girl in conservative Belgium, a dance scene between the young protagonist and another girl currently the object of her inchoate affections pulses with emotional currency and unvoiced desire while James Brown’s ’This is A Man’s World’ plays cruelly in the background.

In Toute une Nuit (1982), a film entirely composed of fragments of nocturnal scenes and late-night meetings over the course of one insomniac evening again in Akerman’s hometown of Brussels, couples either jolt together insistently on makeshift dance floors in cafés, clasped around each other with the timeless and immobile quality of sculptures by Rodin, or sit estranged from one another, on the cusp of making the first move, while lights and music blare in the background. In the latter example, Akerman might be seen to exert a form of what Erin Manning calls “choreographic thinking,” or the exploration of a mode of perception prior to the settling of experience into firmly established categories. Through this sensitivity to minute perceptual inclinations before they are made concrete, dancing in Akerman, then, surfaces less as a mode of deterministic embodiment or as evidence of the body’s unnegotiable materiality than as a means of sketching possible relations, possible routes through the quotidian.

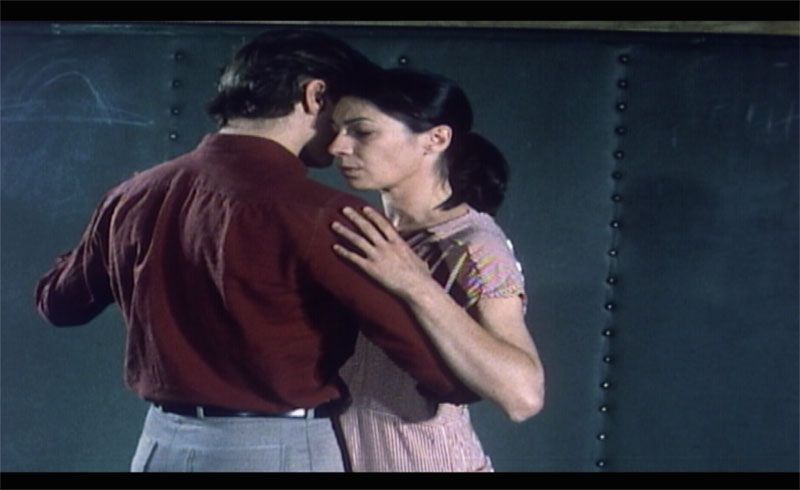

In One Day Pina Asked we see that a key impetus of Bausch is to construct situations where the unexpressed might abruptly burst forth, and cause a tear in the negotiations of the everyday. “One day, Pina came to the studio and asked us what we heard by the term love,” one troupe member explains, early in the feature. Yet ‘love’ is an ambiguous term in relation to Bausch’s work, often proving inaccessible in its opacity. Many of the shards of dances in the film seem—a concern that also patterns Akerman’s own film-work—instead preoccupied with the burlesque violence of relationships between heterosexual partners, and with the clumsy accelerationism of desire, rinsed of traditional ballet’s virtuosity and grace.

Rather than ballet’s vertical focus on the legs and feet, One Day Pina Asked stages a recurring fascination with hands, faces, and mouths as sites of an impossible orality. While there is humour, and often tenderness, in the way that men and women awkwardly edge around each other—a scene in which a male and female performer constantly crash into one another and voraciously embrace recalls Marina Abramovic’s and her long-term partner Ulay’s performed series ‘Relation in Space’ from 1976—a sense of blunt asymmetry pervades this treatment. In one piece, Kontakhof, which is the German term for a place where prostitutes wait to pick up clients, a swarm of men in suits crowd a woman and rehearse a stream of stock, invasive gestures: pulling her hair, tweaking her nipples, pinching her cheeks, as, in the centre, she becomes more and more deranged.

In an interview recorded in 2011 with the critic Nicole Brenez, Akerman was given the challenge of summating each of her forty-four films in one sentence, or one phrase. Of One Day Pina Asked she offered the following formulation: “sadistic horror amidst beauty”. Such is typical of Akerman’s wayward, contrarian nature: constantly perverting expectations, rigorously warding against cliché, at all times. We might, given the historical context from which Bausch’s work is derived, have expected to encounter the inverse evaluation: Beauty amidst sadistic horror. That Akerman frames her film in the opposite fashion demonstrates to what extent, despite its latent darknesses, this is an optimistic feature that defies beauty as a mode of exceptionalism and sees it rather as embedded in the minor gestures that occur on the fringes of large-scale performances. Beauty is the norm, the given, rather than abject brutality. Yet, as Akerman and Bausch’s work suggests, we have to remain open to both.

Alice Blackhurst is a writer and researcher based at King's College, Cambridge. Her PhD explored questions of luxury as aesthetic experience in the work of Chantal Akerman, Sophie Calle, and Louise Bourgeois . Her writing has been published by Another Gaze, The Paris Review, Vogue, and Vestoj, among others. This text was delivered as a reading before the Orlando screening of One Day Pina Asked (Chantal Akerman, Icarus Films, 1983) at the Horse Hospital in April 2018.