All images courtesy of Geraldine Snell

Overlove: A Conversation

Daisy Lafarge and Geraldine Snell

The following is an edited transcript from a conversation between close friends Geraldine Snell and Daisy Lafarge, talking about love, limerence, obsessions, and the literary context surrounding Geraldine’s debut publication—overlove—published by Dostoyevsky Wannabe.

DL: Do you want to give an overview—or underview—of overlove?

GS: overlove is a documentary-cum-literary work consisting of diaristic love letters to a drummer I developed a limerent crush on in November 2016, when I saw him play a gig, and then found him online after. The bones of the letters, addressed to drummer ‘Curt’, were written during my convoluted pursuit of Curt between November 2016 and June 2017, and edited after. overlove subjects Curt to my messy, conflicted female gaze and really deals with love, desire, and malaise through its exploration of being ‘in love’ with (or limerent about) someone you don’t even know while in a monogamous relationship.

DL: Maybe we should explain what limerence is?

GS: It’s funny, you told me about limerence, like you tell me about everything. I think you’re my brain—I just do these things and you give me all these contextual reference points. Limerence is clearly something that never caught on because nobody uses it.

DL: Nobody uses it but I’ve never found a term that describes the feeling so accurately...

GS: Indeed! It is essentially the missing link in the lust-love spectrum. Lust is such an inadequate term for the gravity of what you feel when you’re strongly attracted to someone, and the term crush is often seen as frivolous or teenage...

DL: Or something that you’re never going to obtain. In addition to that light and frivolous meaning, there is also the sense that it can destroy or actually crush you: ‘Man crushed by building’.

GS: Limerence was coined by psychologist Dorothy Tennov in the 1970s about romantic attraction and is characterised by “feelings of euphoria, and the desire to have one's feelings reciprocated”. In terms of overlove, I—or my body, really—perceived potential eye contact and an initial message exchange with Curt as proof that my romantic attraction to him was, or could be, reciprocated, which was completely irrational and delusional, obviously.

DL: It’s as if you’re so aware of anything that might be a sign, that everything is then interpreted as confirmation. And him messaging you was an eruption of potential dialogue into your private realm of fantasy. As a teenager I used to get limerent crushes all the time, sometimes on people I’d never even met, I’d just hear about them and develop all these ideas and wait for them under a tree, convinced they were going to come, feeling like ‘fate was on my side’. When I was 14, I went to PC World with my Gran and really fancied the guy who sold her a laptop. I remember what belt he was wearing, how his hair was, and I looked at his name on his card and went home and found him on MySpace and obsessed over him - for at least a week!

GS: When I was 13, I stayed in France on a family holiday and became heart wrenchingly obsessed with this 17-year old mountain biker. I remember heaving with tears in my room to Queen’s ‘You Take My Breath Away’ when he left, before I remembered he’d mentioned that he worked at Halfords, and I also knew he was from Bury, Suffolk. Egged on by my holiday friend Alice, I called up all the Halfords around Bury and asked for ‘David’.

DL: Did you find him?

GS: No, but I had another brainwave because there was a sign-in book for guests returning from mountain-biking, and his name and mobile number were there! So I texted him and confessed my love, which obviously freaked him out...

DL: The question is, what you do with the desire, the energy? You’ve written a book with it...

GS: I’ve written a book, yeah [laughs]. We often we crush on people we don’t know....

DL: … and on some level you even know you’re projecting onto them. But being able to rationally diagnose that is not as interesting to you as going with the feeling?

GS: Indeed. With overlove I really did ‘go with the feeling’.

DL: It’s interesting how it brings up ‘longing’—whether that’s romantic desire or a childish longing—and that it seems to unleash some block or self-consciousness in writing. The times that I’ve been very limerent I’ve written in this kind of wild mode of longing as a way of expending that energy. We’ve spoken before about the early medieval female mystics writing in this crazed mode of longing for Christ, to be joined with him in union, like Catherine of Siena who wanted to wear his foreskin as a wedding ring…

GS: Jesus...

GS + DL: Literally… Jesus! [laughs]

DL: And having visions of ecstasy. They’re so great to read.

GS: Well that’s it. You can’t dismiss these things, the gravity and energy they trigger is incredible: I was just high off it! I knew it was more about longing than it was about Curt, so I was questioning what exactly I was longing for. If I already have a partner I love, what do I want from this person or pursuit if not hope of transcendence?

DL: I feel like this maybe is partly why limerence, as a term, never caught on, because it attempted to pathologise something that feels so deep and real. In overlove you have this running commentary analysing your emotions as you’re having them, and quite consciously deciding to go with them anyway.

GS: The first letter to Curt begins with apology and analysis, but it ends with a reversion to gut feeling. This is overlove in a nutshell. A self-awareness permeates the whole text, but there’s this constant conflict between wanting to dismiss it and be a good feminist (or merely, a sane adult) and wanting on a deeper level to just obsess, fantasise, and be mirrored by Curt regardless, and at any cost.

DL: I wonder if a psychotherapist might see it as a drama playing out between your child and superego. The child running towards this ideal state of ecstasy with open arms saying ‘Complete me! Love me!’ and the superego’s just like, ‘No. You piece of shit adult!’

GS: Exactly. There’s even an account of a dream I had around February (the middle of the book), which exactly exemplifies that totally innocent desire to be mirrored and held.

DL: The dreams are my favourite bits! I found them so moving; they’re very tender. For me, they back up all the mythic behaviour you begin to explore in waking life. Did you also feel like the dreams had a quality of emotional truth propelling you towards the second encounter with Curt, which forms the narrative peak of the book?

GS: Definitely. I agree that perceived synchronicity is part of the delusion, but I also think that the context of the second encounter with Curt was eerily in sync with my personal journey up to that point. I won’t spoil it, but I really couldn’t have made it up! Of course, though, the whole impetus for overlove came from over-interpretation. At that time, I was feeling lost, creatively suppressed, and attempting to identify with something deeper or more vital than what I was getting through academic study.

DL: That’s an important word: identification. Or to believe that you could leave your cumbersome adult ego behind, be the child that’s completely adored and safe. I guess it’s also embracing your capacity to love.And ultimately you’ve done something creative with what some would term ‘destructive’ energy.

GS: It can’t have been that destructive because at the same time as writing—which did end up clarifying my artistic vision—I was completing a very demanding teaching qualification and landed a teaching job. If anything it gave me more momentum and energy! Around the time I began writing, I watched Anna Biller’s 2016 film The Love Witch and realised that this is it: I don’t really care about things like institutional critique, or how distanced and obfuscating art discourse is in general. I care about love!

DL: I see it as a holistic way of making work, it’s not like you’ve just ‘chosen’ a topic, like institutional critique, which doesn’t really get your blood racing, but something that is lived, intense, bodily, which you can also bring intellect to, and contextualise, analyse. It’s just more...

GS: Fundamental!

DL: More integral to you being a person? I wondered about influences, because I see the letters and books we exchanged in the years leading up to you writing overlove, and my own novel Paul, as a kind of background reading. We were so empowered by the way we saw women writers unlocking stuff that we didn’t know could be literature, which at the time we found very illicit and exciting, like I Love Dick by Chris Kraus, Love Dog by Masha Tupitsyn, Heroines by Kate Zambreno, and the ‘SickSickSick’ reading group we both attended in Glasgow.

GS: It perfectly countered the dry discourse and dissection we felt suppressed by at art school, which encouraged consideration over expression. The vibe was predominantly intellectual; sincerity, sentimentality—everything that is felt not thought—seemed somewhat taboo. This reflects a broader privileging of culture over nature—which is of course as false and gendered a dichotomy as felt/thought is—that I feel informs a the historic dismissal or suspicion of non-male artists. That 1998 Artforum review of I Love Dick as ‘a book not so much written as secreted’ is a badge of honour!

DL: As if anything that oozes from a female is so wrong!

GS: In retrospect, I was influenced by ILD because while I actively avoided the distancing achieved by Kraus’third person accounts, the very fact that a married woman elevated her letters to a crush to a literary work...

DL: With her husband in on it...

GS: It was like, ‘oh right, well of course that’s a valid thing’. Although overlove is way more secreted than I Love Dick!

DL: Yeah, it can be quite cool and measured, whereas overlove is much more immediate, gushing. Although when someone tells you you’re gushing it’s never a compliment.

GS: Yeah, overlove certainly gushed out [laughs]. Anyway, it’s all your fault: you told me about I Love Dick…

DL: So I legitimised this whole endeavour… Well, you shouldn’t trust me!

GS: [laughs] Nah, it’s not just you… I definitely was propelled by the sense that this was ‘meant to be’, and I’m kind of mystical anyway. Because how could you not be? I really felt like Curt had seen me for a reason.

DL: Seen. I think that word is important. You wanted to be seen. You connected with him because you thought he’d seen you: not just a pretty face, but he’d seen your soul, and he thinks you’re a beautiful soul. How did you feel after that second encounter?

GS: Just absolutely high, until the inevitable comedown… [laughs]

DL: You set that up for yourself though. You didn’t just close him off in your fantasy, you actually relinquished some control by allowing his reality to come in and rupture it. He could’ve responded positively and it could’ve carried on. In my experience of limerence, I’ve always waited until there’s a ‘sure sign’. My fear of rejection was so great so I tended to keep them more in a fantasy realm so they had no chance to reject me!

GS: I think I felt like something needed to happen, because I wasn’t going to get any closure until I’d pushed it further. And I also sort of used the crush, and developing the writing and film since, as my raison d’être, my medicine.

DL: Like a pharmakon? A medicine and also a poison.

GS: Exactly. When it became more poisonous than medicinal, I decided to focus on the art of it, to transform it, and myself, creatively.

DL: How far into writing the diary entries did you become conscious that it was going to be a piece that you might publish, and did it change how or what you wrote?

GS: The precedent set by Kraus permitted me to write, but not send, from the start. Initially there was an early entry that alluded to potential publication, but when the bubble first really burst in January I didn’t know where it could go. I felt compelled to see him again and justified it as necessary for the writing. My partner said to invent something and use my imagination, but I thought it was naff to make it up.

DL: Well, you’re more invested in writing the authenticity of it, so you were happy with whatever the narrative outcome was as long as it went somewhere.

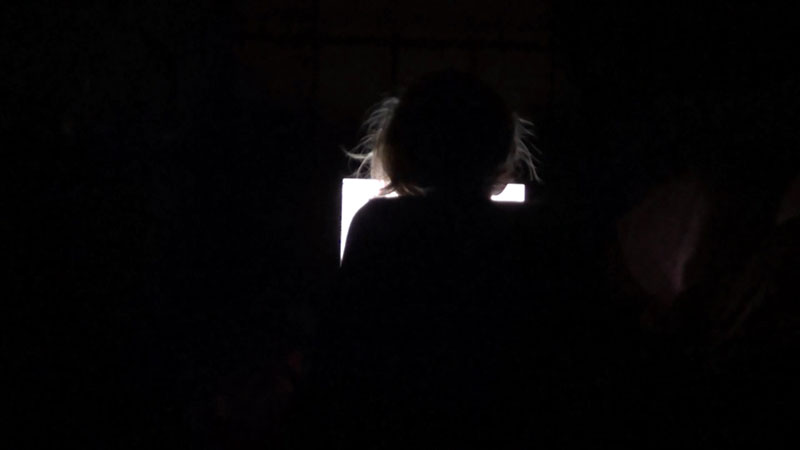

GS: Up to that point it had just been me writing at ‘Curt’ with no feedback, typing into the void. An alternative ending would’ve been to send him the writing and see if he replied.

DL: But I think you had to return to that public setting where it all started.

GS: Yeah... it’s not like my writerly brain fabricated this, my actual body experienced it all and sought Curt again for meaning and direction’s sake. Maybe it’s just life imitating art, but I hope that vitality permeates the writing. What I respond to in art is immediacy and urgency: the sense that someone made something because they were freaking out or feeling too much.

DL: There was an existential question in it. The art may not answer it, but it was an attempt to find or create something that would do instead of an answer, and it needed to be made because someone needed it rather than it just being an affectation or…

GS: Dissection of...

DL: ...some distant, objective research interest or something. Should we have a little break?

GS: Woah, we’ve talked for an hour. Okay.

Further Reading

A Lover’s Discourse Roland Barthes

The Love Witch Anna Biller

A Handbook of Disappointed Fate Anne Boyer

Who is Mary Sue? Sophie Collins

Speculum of the Other Woman Luce Irigaray

I Love Dick Chris Kraus

Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love Dorothy Tennov

Love Dog Masha Tupitsyn

Heroines Kate Zambreno

Geraldine Snell is an artist, writer and musician based between London and Leeds. overlove was published by Dostoyevsky Wannabe in October 2018 and you can find most of her work—including the overlove web series—at geraldinesnell.com. Daisy Lafarge is a writer, artist, and editor based in Edinburgh. understudies for air was published by Sad Press Poetry in 2017. She is the reviews editor at MAP, and writes and teaches at the University of Glasgow.