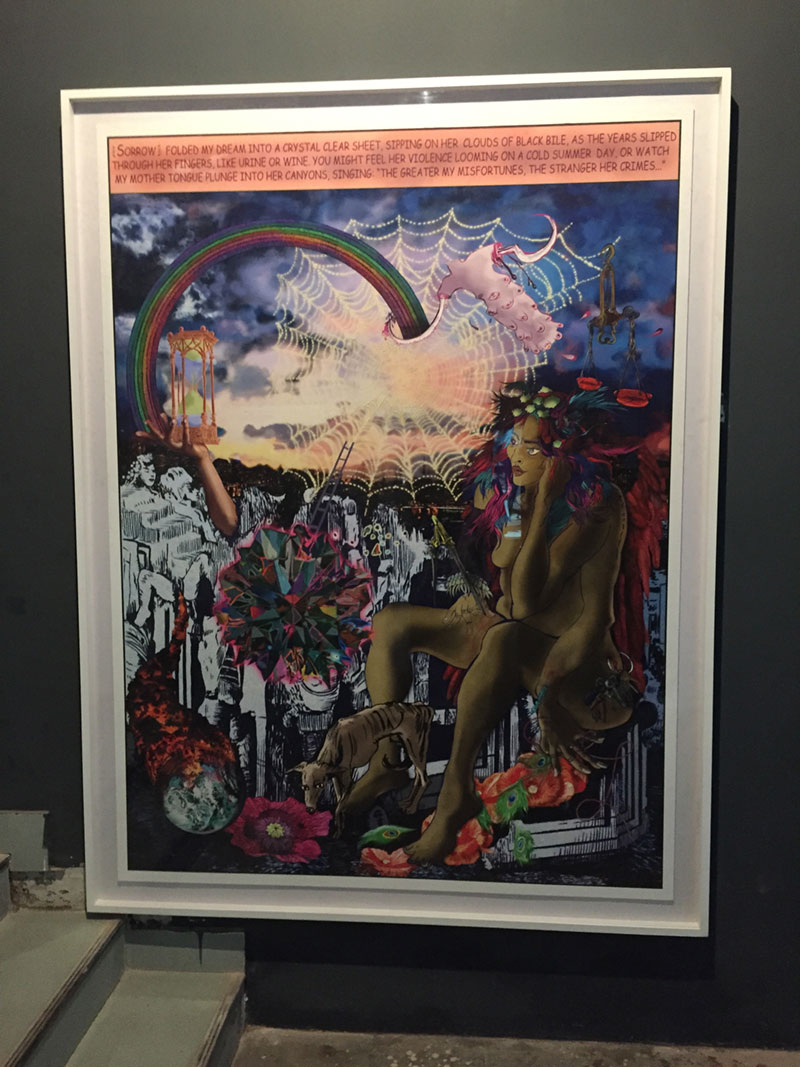

Chitra Ganesh, Melancholia: Sorrow’s Refrain, 2010, photo: Jyoti Dhar

Anoli Perera, I Let My Hair Loose: Protest Series, 2010-11, courtesy of Kochi Biennale Foundation

Mrinalini Mukherjee, Kusum, 1996, courtesy of Kochi Biennale Foundation

Priya Ravish Mehra, Installation view at Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2018, courtesy of Kochi Biennale Foundation

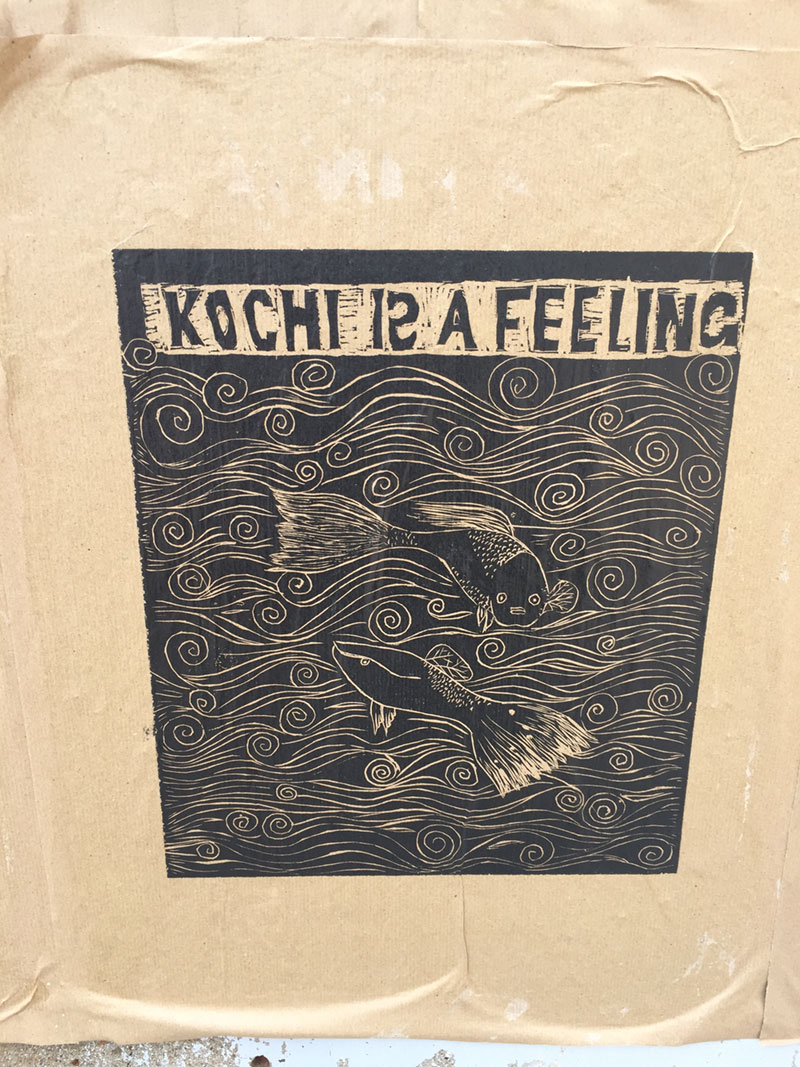

Kochi is a Feeling, Art project by Volunteers of Kochi Biennale 2018, photo: Jyoti Dhar

Kochi is a Feeling (A Non-Review)

Jyoti Dhar

I felt uneasy from the get-go. There had always been some kind of rumour and speculation circling the Kochi Muziris Biennale—usually to do with whether India’s largest not-for-profit art event, staged against the odds, would be able to pull it off or not—but that’s not what my sense of worry was about. This time it was different. This time it was more personal. Heading to Kochi for the fourth edition of the biennale, I felt a sense of unease (or was it a kind of dis-ease, a mal-aise, or being out of sorts) in my body. It was difficult to diagnose exactly, but it stemmed from a sense of disconnect.

The lead up to the biennale had been particularly disruptive. One of its co-founders, Riyas Komu—who was part of the ‘Bombay Boys’ group of artists back in the ‘90s and was now considered to be a major curator in South Asia—had stepped down after being accused of sexual assault. The allegation against him, and several other prominent members of the Indian art community, was made anonymously by a group of survivors on an Instagram account called ‘Scene and Herd.’ What was potentially a moment of empowerment and solidarity for women in the art world became a point of division, mistrust, and disbelief.

The division, at least on social media, appeared to be between different generations of feminists, questioning the use of violent language, fixed positions, and call-out culture. The mistrust seemed to be of the virtual space, the idea of anonymity, and accountability. The disbelief was harder to fathom, especially as in many cases the aggressors had multiple accusers. These conversations were heightened and propelled by the backdrop of a biennale curated for the first time by a woman—Anita Dube—a queer feminist who actively sought to include the work of marginalised people and groups.

Addressing this context head-on in her curatorial speech, Dube called for the biennale to be a forum where we could face each other, listen to one other, and voice our differences. She talked about an ‘eros of sharing’ and the need to deconstruct power. However, beyond the class-continuous space of the Delhi and Mumbai art-worlds, she also looked to address issues grounded in the time, place, and wider audience of the biennale. It was a tall order. Was it up to one exhibition to do all of these things? To embody discourse, critique the current system, and speculate on possible futures?

As we walked through the exhibition on the curatorial tour, I wondered if we could think of it another way. Dube’s exhibition was bookended with an evocation of the body: from the notion of rupture, repair and invisible labour in Priya Ravish Mehra’s exquisitely stitched organic fragments, to the sumptuous and sensual hemp sculptures by Mrinalini Mukherjee, boldly celebrating the female and natural form. It struck me that these artists’ politics, much like Dube’s, was not what was on display, but latent in the way they lived their lives. Feminism and activism are after all ‘living campaigns’.

What if we were to extend this idea of the ‘living campaign’ to think of the biennale too as a form of living? As a body, perhaps, with its all its vulnerability and responsibility? Could we think of it as something inclusive of flaws, and that could change over time? As I was wondered this, a curator friend suggested that the part with Mukherjee’s sculptures could be seen as the ‘brain of the show’—a site from which many of the conceptual and formal threads radiated outward. Chittaprosad Bhattacharya and KP Krishnakumar’s drawings, placed alongside, were certainly symbolic of the show’s radical and leftist impulses.

This is not to say, however, that there was an emphasis on the moralistic or the didactic in this biennale. Rather, from the immediacy and ephemerality of Song Dong’s interactive water-painting, to the generosity and complexity of William Kentridge’s dancing animation, there was a foregrounding of the affectual and the intuitive. At the ‘heart of the show’ was a stunning array of art by women (a stark contrast to the fact that the inaugural edition only had nine women). From Shirin Nishat to Monica Mayer, Nilima Sheikh to Anoli Perera, their work sang to you, spoke to you, left an imprint on you.

The collective impact of such work reminded us that feminism has never been one thing or had one method. It is meant to evolve through debate and argument. As critic Katy Deepwell says in the text, Feminist Critique: Open and Critical Enquiry (2015), “feminism has always been a heterodox, open, complex, and contested field about women and, in relation to art, art criticism and art history as well as women’s studies, feminist theory and activism in the women’s movement.” Perhaps this is why Dube chose work by women that also intersected with regional ecologies (Marziha Farzana), nationalisms (Shilpa Gupta), and futurisms (Chitra Ganesh), in innovative ways.

To challenge the prevailing systems of patriarchy and cultures of abuse, it is not enough to simply curate more women, or include voices from the margin. It is imperative to create conditions in which the ‘queering of subjectivities’ can be allowed for, opening up the potential for real dialogue and empathy for the other. Dube’s biennale achieved this not only through its multiple programs with local women’s groups, but also through its especially commissioned pavilion —the lungs of the show, perhaps—a place for porosity, fluidity and exchange. And it was here that a group of art practitioners finally addressed the collective unease we realised many of us had been feeling in different ways.

After a Guerilla Girls performance, the group stood up and asked the biennale foundation directly if it would take the allegations seriously, protect anonymity of survivors, and set up systems to ensure safe work spaces for women. Amazingly, the entire pavilion stood up in solidarity. Even if it was a naïve and transient drop in the ocean, it felt like a certain consciousness had been raised—by Scene and Herd, by Dube, and maybe by the group—all of whom may have disagreed on what the notion of feminism might mean to them, but all of whom were able to find common ground when it counted. “A lone revolutionary does not make a revolution,” Dube had reminded us in her opening speech. “It is not spontaneous, it takes hard work. We have to work collectively to make real change.”

Jyoti Dhar is an art critic based between New Delhi and Colombo. Her writing focuses on women artists from South Asia, and the intersection between art and psychotherapy in post-conflict Sri Lanka.